By Maureen Storey

This article was published in the August 2020 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

William Stinson Soule, the son of John and Mary (neé True) Soule, was born on 26 Aug 1836. He spent his childhood on the family farm just outside Turner, Maine. Little is known of those early years but by 1861 William was working in Boston in the photography business of his older brother, John Payson Soule.

At the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, William enlisted in the Union Army, serving in Company A of the 13th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers. The regiment was involved in major campaigns in Virginia throughout the first year of the war, but its severest test came at the Battle of Antietam on 17 Sep 1862. Although Antietam is counted as a Union win, the poor tactics of Major-General George G McClellan, who was leading the Union Army, meant it was far from a decisive victory. Antietam was the bloodiest single-day battle in US history with a total of 22,717 dead, missing and injured, the majority of whom came from the Union Army. William’s regiment was reported to have lost 600 men, nearly its entire strength, in just 20 minutes. William was one of the wounded, having been struck in the hip by a Minié ball. He was evacuated first to a field hospital and then to a base hospital in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Though he never fully recovered from the injury, William eventually returned to his regiment. In September 1864 the regiment completed its term of service and most of the men left the army. William, however, reenlisted, joining the Invalid Corps, which consisted of men who were unfit for field service but who could undertake administrative duties.

In 1865 William returned to photography and set up a studio in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where a large part of his work came from soldiers and veterans who wanted pictures to send back to their families. The business was doing well until the studio was partially destroyed in a fire. At this point William decided it was time to move on, so he sold his premises and used the proceeds to buy a new camera and darkroom supplies and went west. He travelled first to St Louis, from there to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and then to Fort Dodge, Kansas, a new Army post on the Arkansas River route (the old Santa Fe trail). While there, though he spent his spare time honing his photography skills, he worked in a sutler’s office. (A sutler was a civilian who followed the Army and sold supplies to the soldiers.) After about a year he moved again, this time to Camp Supply, Oklahoma Territory, but stayed only a few months. In 1869 William accepted a job with the Engineers Corps and became the first official photographer of Fort Still, a new Army camp that was being built in Oklahoma territory. William’s brief was to document the building of the fort and the development of the surrounding area.

Much of the work that William did for the US Army still survives, as do his photos of the fort personnel and their families, but it is for his photos of the Plains Indians that he is most famous. By the time William arrived in Fort Sill, the Plains Indians had been defeated in the bitterly fought Indian Wars. However, the tribes had not yet been moved to reservations and were still living much as they had before the arrival of the white man. William’s pictures of their lodges and huts are nowadays closely studied for what they show about Native American culture, but it is his portraits that capture most people’s imagination. About 70 of his photos survive, not just of chiefs and warriors but also some of women and children and include representatives of the Kiowa, Apache, Cheyenne, Wichita, Caddo, Arapaho, Navajo and Comanche tribes. They show a still proud people, who though somewhat wary of photography (they called photographers shadow-catchers) were intrigued enough by it to be happy to have their photographs taken.

Unlike many later photographers who dressed their subjects to reflect what was regarded as ‘Indian dress’, William’s portraits record his sitters exactly as he found them, so there is a mixture of traditional buckskins and feathers and western clothing and hats. He has clearly tried to capture as many aspects of their life as possible, so the subjects include people in summer and winter clothing, a chief (Chief Powder Face) wearing a full length war bonnet and carrying a lance, a Navajo silversmith with his tools, family groups and children.

In about 1874 William went to Washington with a delegation of Native Americans to meet the president and there he met his future wife, Ella Augusta Blackman. The couple decided that they didn’t want to set up home in the Indian Territories and so William returned to Fort Still to settle his affairs and to fetch his photographic equipment, He found to his dismay that an associate had left the camp, heading for California, with all his equipment and most of his photos. William never saw those photos again, though 69 of them turned up in Los Angeles County Museum some 80 or 90 years later.

The theft left William virtually penniless and he had to give up photography for a while and find another way of earning a living. He and Ella moved first to Philadelphia and then to Vermont, where eventually he saved enough money to be able to restart his photography career. In 1882, he returned to Boston with his wife and two daughters and bought The Soule Art Company from his brother John. (It was John’s turn to ‘go west’ and he eventually settled in Seattle ,where he set up a new photographic company.) William stayed in Boston until retiring to Brookline, Massachusetts, in about 1900. He died in Brookline on 12 Aug 1908.

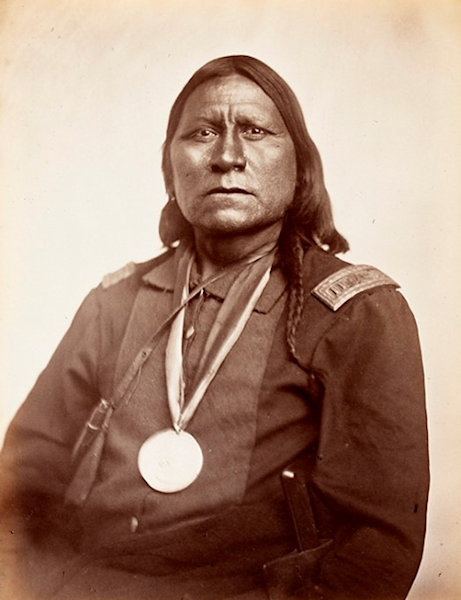

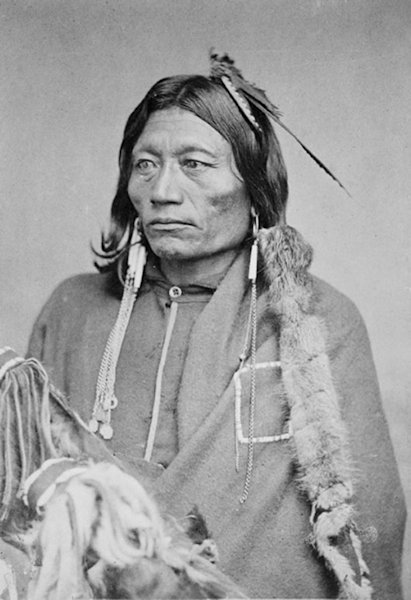

Native Americans on this page photographed by William Soule

Satanta, White Bear, was a Kiowa war chief, this photo taken at Fort Dodge in spring, 1867. Satanta, was born about 1820 and was renowned for his prowess as both a warrior and an orator. He was part of a delegation of Indians who went to Washington to meet President Grant to discuss a peace treaty.

Essa-queta, Pacer (Peso), for many years was a chief of the Kiowa-Apaches. He was considered to be a man of considerable intelligence and ability. He was a consistent advocate of peace.

Esa-habert, Bird Chief, an Arapahoe chief. He led a raiding party into Kansas in the summer of 1872.

Black Hawk, a Kiowa-Apache. Little is known about him except that he had a reputation for being friendly and cooperative.