By John Slaughter

This article was published in the August 2015 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

We continue the edited version of the talk John Slaughter gave at the 2014 Annual Gathering.

U-Boat Campaign

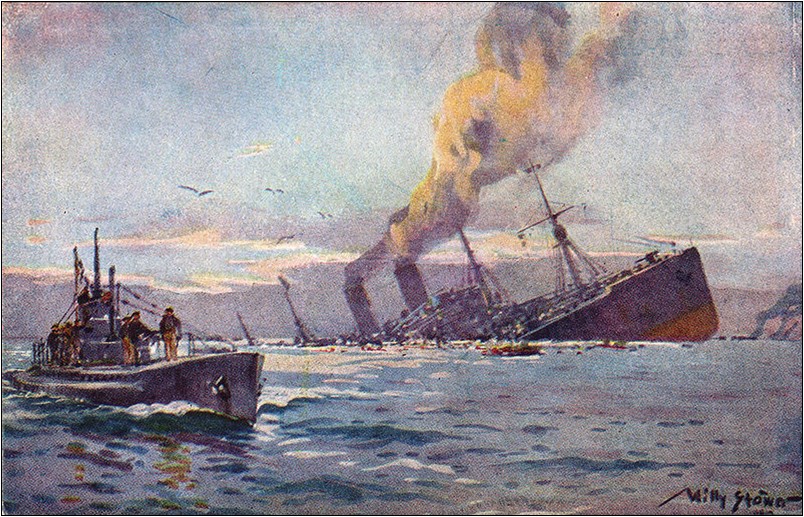

One of the features of the War at Sea was to try and blockade the enemy and deny them imports of food and raw materials to supply their war industry. As we had seen Britain was quite effectively able to do this with their dominance in the North Sea with surface based warships. Germany’s attempt at blockade was by using U-Boats. On 4 February 1915 the Commander of the German High Seas Fleet published a warning in the Imperial German Gazzette. It read:

(1) The waters around Great Britain and Ireland, including the whole of the English Channel, are hereby declared to be a War Zone. From February 18 onwards every enemy merchant vessel encountered in this zone will be destroyed, nor will it always be possible to avert the danger thereby threatened to the crew and passengers.

(2) Neutral vessels also will run a risk in the War Zone, because in view of the hazards of sea warfare and the British authorization of January 31 of the misuse of neutral flags, it may not always be possible to prevent attacks on enemy ships from harming neutral ships.

Following the declaration of ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’ the tonnage of shipping sunk by U-Boats steadily increased throughout 1915. The most noteworthy casualty occurred on 7 May 1915 when the liner RMS Lusitania was torpedoed 32 miles of the coast of Ireland and sank in just 18 minutes. Of the 1,959 people of board, 1,198 were killed, 128 of them US citizens. The resulting outrage in America nearly led the US to enter the War at that stage. US President Woodrow Wilson sent three separate notes to the German Government in May, June and July 1915 making the US position clear. In the third note he issued an ultimatum to the effect that the US would regard any subsequent sinkings as being ‘deliberately unfriendly’. The American public and leadership were not ready for war at that time, but the sinking of the Lusitania had started them on the path to war.

Allied countermeasures to the U-Boat threat had mixed success. At the start of the War surface ships had no means to detect submarines and no means to attack even if they could do so. The development of the Depth Charge had first been mooted in 1910 and went into preliminary production in 1914. However, it was not until January 1916 that an effective Depth Charge became available, the first successful sinking of a U-Boat took place of the coast of Ireland on 22 March 1916. However, during the whole of 1916 only 5 U-Boats were sunk by Depth Charges.

Jutland

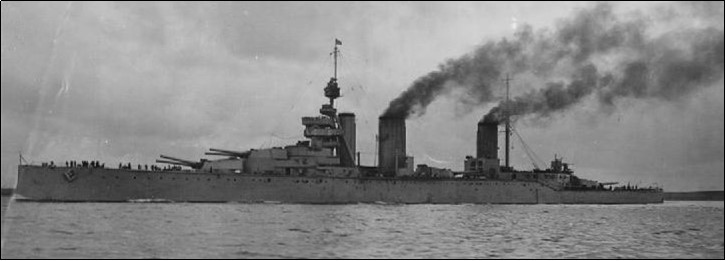

The next major event was the Battle of Jutland fought between the British Grand Fleet (supplemented by ships and personnel from the Australian and Canadian Navies) against the German High Seas Fleet. The battle was fought on 31 May and 1 June 1916 in the North Sea near Jutland, Denmark. It was the largest naval battle and the only full-scale clash of battleships in the war.

The Grand Fleet was commanded by British Admiral Sir John Jellicoe and the High Seas Fleet by German Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer. The High Seas Fleet’s intention was to lure out, trap and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, as the German naval force was insufficient to successfully engage the entire British fleet. This formed part of a larger strategy to break the British blockade of Germany and to allow German mercantile shipping to operate. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy pursued a strategy to engage and destroy the High Seas Fleet, or keep the German force contained and away from Britain’s own shipping lanes.

The German plan was to use a fast scouting group of five modern battle cruisers to lure a British battlecruiser squadron into the path of the main German fleet. Submarines were stationed in advance across the likely routes of the British ships. However, the British learned from signal intercepts that a major fleet operation was likely, so on 30 May Jellicoe sailed with the Grand Fleet to rendezvous with Admiral Beatty, passing over the locations of the German submarine picket lines while they were unprepared. The German plan had been delayed, causing further problems for their submarines which had reached the limit of their endurance at sea.

On the afternoon of 31 May, Beatty encountered the German battlecruiser force long before the Germans had expected. In a running battle, the German battleships successfully drew the British vanguard into the path of the High Seas Fleet. The British were silhouetted against the western horizon, smoke obscured the German ships and British gunnery was dreadful – so the Germans inflicted early blows. A shell penetrated a gun turret aboard HMS Lion, Beatty’s flagship, causing a fire in the magazine below, which could have destroyed the ship had the compartment not been flooded, drowning all inside.

Moments later, a shell sliced into HMS Indefatigable’s forward turret. No-one had closed the magazine doors and the ship blew up in a catastrophic explosion, killing all but two of 1,019 men aboard. Shortly afterwards, HMS Queen Mary exploded, taking with her nearly 1,300 men and prompting Beatty to say ‘there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today’.

As Beatty pursued Admiral Hipper south, the German battlecruisers came under heavy fire from Beatty’s four 15 inch gunned ‘superdreadnoughts’, until at 4.33pm the British spotted Scheer’s High Seas Fleet. Beatty turned away, hoping to lure the Germans back north to Jellicoe, who was steaming towards him, ‘wishing someone would tell me who is firing and what they are firing at’. The confusion was deepened by German Rear-Admiral Horace Hood, who led his three battlecruisers and their escorting ships towards the enemy.

As Hood pushed forward, the light cruiser HMS Chester was repeatedly hit and Jack Cornwall (aged 16) was horrifically wounded. He died after the battle and became the youngest recipient of the Victoria Cross.

Finally, at 6.14pm Jellicoe received a signal from Beatty and ordered his ships into a battle line as the mist cleared, exposing Hood’s battleships to overwhelming German fire. A shell hit one of HMS Invincible’s turrets. Again, the flash raced into the magazines and she vanished in a huge explosion.

Fourteen British and eleven German ships were sunk, with great loss of life. Amongst these were Able Seaman Frederick William Solly on HMS Invincible and Gunner Herbert Sewell on HMS Indefatigable. After sunset, and throughout the night, Jellicoe manoeuvred to cut the Germans off from their base, hoping to continue the battle the next morning, but under the cover of darkness Scheer broke through the British light forces forming the rear guard of the Grand Fleet and returned to port.

Both sides claimed victory. The British lost more ships and twice as many sailors, and the British press criticised the Grand Fleet’s failure to force a decisive outcome, but Scheer’s plan of destroying a substantial portion of the British fleet also failed. The Germans’ continued to pose a threat, requiring the British to keep their battleships concentrated in the North Sea, but the battle confirmed the German policy of avoiding all fleet-to-fleet contact.

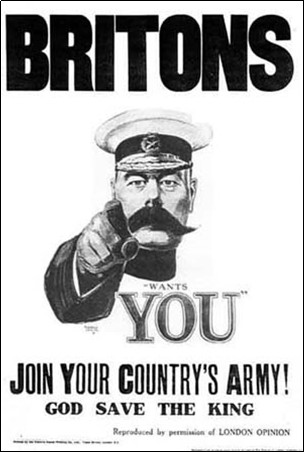

Death of Kitchener

Just a few days after the Battle of Jutland HMS Hampshire, which had a very minor role in the Battle, was sailing to Russia, carrying the Secretary of State for War, Field Marshall Lord Kitchener, when it is believed that she struck a mine laid by a German U-Boat, and sank with heavy loss of life, including Kitchener and his staff. He was succeeded in that post by David Lloyd George.

Unrestricted Submarine Warfare

On 1 February 1917 Germany resumed its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. The British Naval blockade of Germany was causing a food scarcity and deaths from malnutrition there. The war on the Western Front was in a stalemate and military advisers persuaded the Kaiser that a German victory could only be achieved by a blockade of British shipping. The policy initially achieved success, nearly 500,000 tons of shipping was sunk in both February and March, and 860,000 tons in April, when Britain’s supplies of wheat shrank to 6 weeks’ worth. Germany knew that one of the dangers of unrestricted submarine warfare was that the sinking of American shipping could result in the US entering the war. This duly happened when on 6 April 1917 the US Congress declared war on Germany.

The Allied response to the U-Boat threat was the establishing of convoys. In May and June, a regular system of transatlantic convoys was established, and after July the monthly losses never exceeded 500,000 tons, although they remained above 300,000 tons for the remainder of 1917. Convoys brought their warship escorts in contact with attacking U-boats, leading to an increase in U-boats destroyed.

Zeebrugge

The Belgian port of Zeebrugge had for some years been seen as a potential target for a British attack and several attempts to close the port by bombardment had failed. In 1918 a plan was devised by the Allies to block the port by sinking obsolete ships in the canal entrance, to prevent German vessels being able to leave port. The first attempt was cancelled at the last moment, due to unfavourable weather. A second attempt was made on 23rd April. The plan involved sinking three old cruisers and with two old submarines, filled with explosives, to blow up the viaduct which connected the mole to the shore. It was also intended to land a small force of 200 Royal Marines at the entrance to the Canal to destroy German gun positions. The latter plan failed as the HMS Vindictive, carrying the marines, became visible after a wind change blew away the smokescreen. One of the submarines however did find its target and destroyed the viaduct. Two of the cruisers were sunk in the narrowest point of the canal but the third hit an obstruction prematurely and had to be scuttled. None of the blocking ships were in the planned positions and it took the Germans only a few days to dredge a channel around the ships and allow U-Boats to pass out of the port.

Despite this failure however the raid was hailed by Allied propaganda as a British victory and eight Victoria Crosses were awarded. It is said that 1700 men took part in the Raid of which 227 died and 356 were wounded. The Germans lost 8 dead and 16 wounded.

End of War

The terms of the Armistice included the internment of the German Fleet and the surrender of all German submarines. There was some disagreement between the Allies as to how the internment of the German surface fleet was to be achieved. The Americans suggested that the fleet be interned in a neutral country but both the countries approached, Norway and Spain, refused. Instead, it was decided to intern them at Scapa Flow, with a skeleton German crew, guarded by the Grand Fleet. The surrender of the German Fleet and those of its Allies took place on 21 November 1918 and amounted to 370 ships.

Negotiations over the fate of the ships were under way at the Paris Peace Conference. Under Article 31 of the Armistice the Germans were not permitted to destroy their ships. Both Admirals Beatty and Madden had approved plans to seize the German ships in case scuttling was attempted; Their concern was not without justification, for as early as January 1919, von Reuter mentioned the possibility of scuttling the fleet to his chief of staff.

The signing of the Treaty of Versailles was scheduled for noon on 21 June 1919. Around 10:00 a.m. on that day von Reuter sent a flag signal ordering the fleet to stand by for the signal to scuttle. At about 11:20 the signal was sent. Scuttling began immediately. Of the 74 German ships in Scapa Flow, over 50 were sunk. The remainder either remained afloat or were towed to shallower waters and beached. The beached ships were later dispersed to the allied navies, but most of the sunken ships were initially left at the bottom of Scapa Flow, the cost of salvaging them being deemed to be not worth the potential returns, owing to the glut of scrap metal left after the end of the war, with plenty of obsolete warships having been broken up. Today just seven wrecks remain and are scheduled. Divers are allowed to visit them but need a permit to do so.