By Maureen Storey

This article was published in the August 2016 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

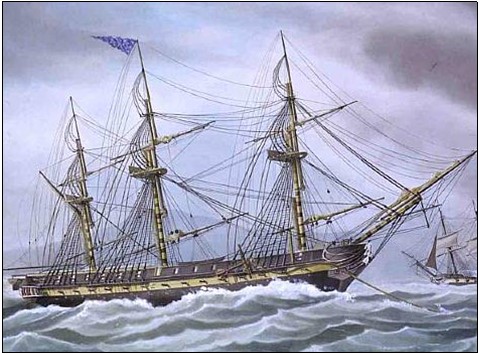

On 16 March 1814 the Adeline, an American schooner operating against British shipping under letters of marque, was captured off Cape Finisterre by HMS Magicienne, a fifth-rate frigate. The Adeline was taken as a prize and her crew were sent to the derelict ships in Plymouth Dockyard that were being used to house American prisoners. Among the crew were Enos Soule (listed in the British records as Elias), aged 20, his brother Thomas, aged 34, both of Freeport, Maine, and Edward Soule, aged 30, also of Freeport, who was probably their first cousin.

The taking of the Adeline was one of the many naval skirmishes in the war between Britain and the United States that became known as the War of 1812. As is often the case the causes of this war were not straightforward. In efforts to defeat Napoleon, Britain maintained a blockade of his European ports, thereby interfering in the trade between Europe and neutral countries like the United States. As part of this blockade the Royal Navy boarded any neutral merchant vessel it found to check its cargo and destination, turning back or impounding any destined for territory under Napoleon’s control. But, after many years of war, the Royal Navy was permanently short of men, so it also took the opportunity to press any British nationals found on these vessels. And since it was not always easy to determine who was British and who was American, many American nationals (some claim as many as 10,000) found themselves serving unwillingly in the Royal Navy. The US government’s complaints about the treatment of its seamen were largely ignored and on 12 June 1812 US President James Madison declared war on Britain.

Although the reasons for the war cited by Madison were the disruption to US trade caused by Britain’s blockade of Europe and the impressment of US nationals in the Royal Navy, there was also an element of opportunism in his action. He thought that while Britain was heavily involved in the war in France it would be unable to defend its North American territories. Therefore, having declared war, he set out to annex Canada. Britain immediately blockaded the US eastern seaboard, causing massive disruption to US trade. There were also several bloody land battles around the US-Canadian frontier and in the US mid-west, where Britain formed an alliance with the Native American confederacy led by Tecumseh. Until the war in Europe ended in 1814, Britain’s actions were largely defensive, but Napoleon’s defeat in 1814 meant that Britain then had the capability of sending large numbers of battle-seasoned troops to America. However, by this time both sides wanted peace and the war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on 24 December 1814.

So what happened to our three Soule sailors after their capture in 1814?

What to do with prisoners-of-war was a problem throughout the Napoleonic War. Initially many were kept in the hulks that littered the Royal Navy’s dockyards. However, this was hardly ideal, partly due to the potential dangers posed by the hulks’ proximity to the dockyards but mostly because the living conditions on the grossly overcrowded hulks were appalling. In 1805 a solution for the prisoners held at Plymouth was put forward by Dartmoor landowner Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt. He suggested that some of his land could be used for a camp. It was agreed that in return the prisoners would be put to work reclaiming moorland for agriculture.

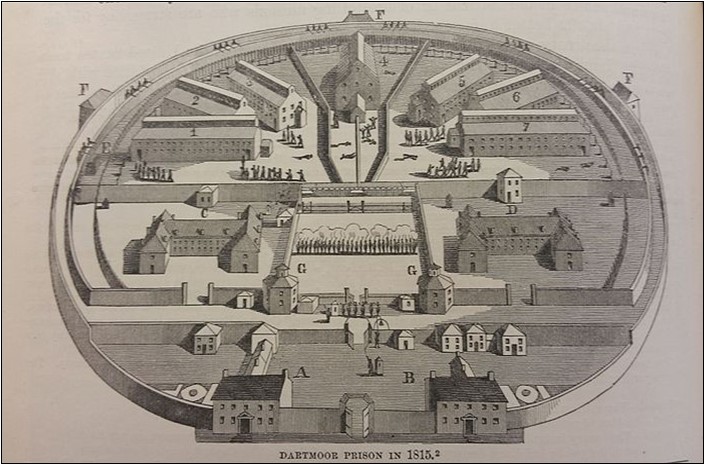

The prisoners built their own prison, a task that took three years. Using granite from Tyrwhitt’s quarries they constructed a 16-foot outer wall that enclosed the 30-acre site. Inside this and about 30 feet from it was an inner wall, which surrounded five large stone buildings. Each of these buildings was intended to house 1500 men, who slept in hammocks slung from iron pillars. In addition, there was a hospital, a governor’s house and some staff quarters. For the prisoners the conditions on Dartmoor were grim, but better than on the hulks.

Britain’s difficulties with coping with prisoners-of-war were further exacerbated when the United States declared war. At first, the American sailors that landed at Plymouth were sent to the hulks recently vacated by the French prisoners. However, once again these rapidly became grossly overcrowded and disease-ridden and the decision was made to send the Americans to the camp on Dartmoor. The first batch of 250 US prisoners was transferred from the hulk Hector in April 1813. Thereafter the number built up until by Mar 1815 there were about 6500 Americans, comprising naval prisoners and impressed American seamen who had been released from service on British vessels. After the first few weeks when they were allowed to mix, the French and US prisoners were kept separate. Although the British were in overall control of the camp, each group of inmates established its own governance and culture. They had courts that punished those who broke their rules, they established in-prison markets and even ran a theatre and a gambling room.

Whilst an improvement on the hulks the conditions were still extremely harsh. Most inmates had inadequate clothing, the prison buildings were largely unheated in what proved to be an extremely hard winter, and the food provided was very poor. Sickness was rife and many died. The crew of the Adeline were sent to Dartmoor in the spring of 1814. By then the conditions for the prisoners had begun to ease a little as the Americans began to receive some supplies from their families back home. They were also once again being allowed some contact with the French, enabling trading between the two groups, but it was the warmer spring weather that brought the greatest improvement.

Life in the prison improved further when the peace treaty with France was signed in 1814 and the repatriation of the French prisoners began. This eased the overcrowding and by August life was far more tolerable for the Americans. However, there was still no sign of them being released. As autumn turned to winter desperation led to several unsuccessful escape attempts, including the digging of two tunnels. Then, on 29 December came the news that the Treaty of Ghent had been signed and the men were told that once the treaty had been officially ratified they would be repatriated. Because of the time it took for news to travel back and forth across the Atlantic it was expected that the ratification would be confirmed in three months.

With the onset of winter the conditions in the camp rapidly deteriorated and another epidemic spread through the prisoners, causing many more deaths. Then on 14 March 1815 came the news that the treaty had been ratified. The prisoners were, however, to experience one final tragedy. On 6 April the captain of the guards found a hole in the wall that separated two of the prison yards. On high alert because of the earlier escape attempts he posted sentries along the walls, the alarm bells were rung and drummers beat the call to arms. The prisoners poured out of the barrack blocks to see what the commotion was about. The guards thought they were coming under attack and charged the prisoners with fixed bayonets, and then the order was given to open fire. The incident, which became known as the Dartmoor Massacre, left 8 men dead and 44 badly wounded. It is still not clear whether the tragedy was due to an over-reaction of the guard captain or whether this really was an attempted mass breakout, though the subsequent enquiry exonerated the guard captain.

On 19 April the first contingent of prisoners was marched to Plymouth to join the boats that would to take them home.

Edward, Thomas and Enos Soule were discharged from the prison with the rest of the Adeline’s crew on 28 Apr 1815 and returned to Freeport, Maine. It has not yet been possible to definitely identify Edward Soule, but he was probably the son of Cornelius Soule and Abiel Prince. Thomas and Enos were sons of Barnabas Soule and Jane Dennison. On returning home Thomas once more went to sea. He married twice and had three children but he never fully recovered from his experiences in the prison camp. He committed suicide in 1824. Enos also went back to sea and rose to be captain of some of the largest ships in Maine. He and his wife Sarah Pratt had 12 children. On retiring from the sea, Enos went into the ship-building business with his brothers Henchman and Clement. Between 1839 and 1879 the Soule Brothers shipyard built 30 sailing ships. Some were sold but most were operated by the brothers in a network that spread around the world.

There was one other American So(u)le held in Dartmoor but the British records do not give enough information to be able to identify him. Does anyone recognise John Sole, aged 24, prize master, who was captured on 26 Apr 1814?

The camp on Dartmoor was closed once the last Americans left in 1816. It remained empty until 1850 when it was reopened as a prison for criminals. Ironically its first inmates were mostly sick and disabled and were sent to Dartmoor for their health! Initially they were housed in the buildings vacated by the Americans and French but over time these were demolished and replaced by the Victorian prison that is still in use today.

Inside the prison walls are two cemeteries, one nominally for the French and one for the Americans (‘nominally’ because when the bodies were reburied in the 1860s, it was not possible to be certain who was who). In 1926 an organisation called ‘The United States Daughters of 1812’ paid for a memorial gate and plaque to be erected at the entrance to the American cemetery. The plaque reads:

To The Glory of God and in Loving Memory of the Two Hundred and Eighteen American Soldiers and Sailors of the War of 1812 Who Died Here.

From this it can be presumed that 218 bodies were buried in the American cemetery, but in fact according to the records 271 Americans died in the camp. As the memorial is inside the prison, for many years it was only ever seen by the inmates and guards. However, the cemetery has recently been tidied up and a visit can be arranged through the Dartmoor Prison Museum.

Did British prisoners of the War of 1812 fare any better in US hands? On the whole, the answer is probably ‘yes’, though this may be just because the number that the United States had to deal with was far smaller. Many British prisoners seem to have been paroled, and were either allowed to live in the community or put under the care of paroled British officers, though some were held by US forces. The American lists of British prisoners-of-war record seven men of interest to the Society, though their details are scant and it may not be possible to identify them. They were:

Edward Saul: he was a boy, serving on the Lapwing, captured by the Rattlesnake whilst at sea on 28 June 1813. he was paroled and sent to the Lapwing

Thomas Saul: he was serving with Sir Edward Pellow and was captured by the schooner Macedonian at Salem on 25 Nov 1814. He was delivered to Lt S Spencer on board Cartel(?) Union

William Saul: he was on the packet Ann which was captured by the York Town on 22 May 1814. He was released on parole to Captain A Riker

William Sowal: he was a seaman on the transport Trident, and was captured by the Johnson, on 25 Jan 1815 in Lake Borgne. He was delivered to J Peddie AQM Gen B Army held at New Orleans

John Sewell: he was a seaman on the Montezuma, and was captured by the US frigate Essex. He was paroled at sea and liberated at Tumbez(sic)

John Sewell: he was captured by Com McDonough at Lake Champlain on 11 Sep 1814. He was delivered to Lt Mark Raynham, Royal Navy

James Sowell: he was the captain’s clerk on the packet Swallow, and was captured by the frigate President on 15 Oct 1812 whilst at sea. He was held at New London and was delivered to Jas Stewart, esq