By Dr David Davis

This article was published in the December 2014 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

This is the write-up of the talk given at this year’s Annual Gathering. Dr David Davis is the former chairman of the Naval Dockyards Society.

By definition, Naval Dockyards were run by the Navy and contained a dry dock. Royal Navy Dockyards were owned by the crown.

Where were the Yards?

The Home Yards:

Deptford (closed 1869, currently being excavated prior to development)

Woolwich (closed 1869, little remains)

Chatham (closed 1984, still a Historic Dockyard)

Sheerness (closed 1960, some remains)

Harwich

Milford – only a Dockyard for one year

Pembroke Dock (closed 1926, built 250 ships for Royal Navy, 5 royal yachts

Haulbowline (closed 1921)

Portsmouth

Plymouth (= Devonport)

Rosyth

Plymouth and Rosyth are the only Dockyards which remain open today.

The overseas Yards:

Gibraltar

Halifax

Jamaica

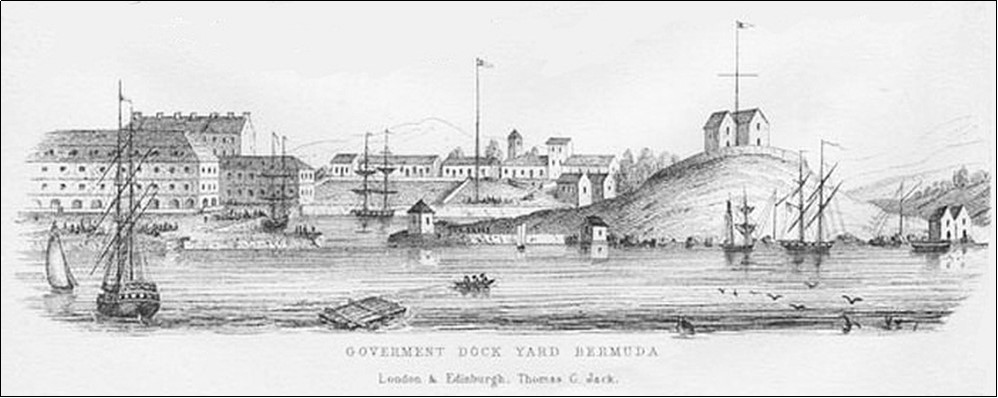

Bermuda

Trincomalee

Bombay

Malta

Equimault

Antigua

Singapore

Hong Kong

Simonstown

The problem for family historians is that many workers moved between dockyards although some did stay for generations.

There were Naval bases (not Dockyards) at Deal, Falmouth (Mylor), Kinsale, Great Yarmouth, Lough Swilly, Berehaven, Scapa Flow, Cromarty, Firth/Ivergordon, Portland and Faslane (HMNB Clyde). Some Naval dockyard personnel lived both in the dockyards but also in Naval bases.

Why were they important?

From 1700s until the 1900s Naval Dockyards were the biggest industrial centres in the country, perhaps in the world. For example in 1694 Chatham employed 1400, at a time when the biggest mill employed maximum of 50. During WW2 Portsmouth Dockyard employed 27,000, by 1963 it was down to 12,000 and by 1981 7,500. Pembroke Dockyard employed 4,000 during WW2.

Working practices in use in the dockyards spread to the external workforce. For example use of clocks to determine the time of beginning and end of day were first installed the Dockyards. Prior to WW1 women were employed in jobs normally reserved for men. For example in 1903 Pembroke Dockyard had women employed in Tracing Department (copying) – an innovation in working practices.

Who worked there?

The most basic jobs were those who dug out the dry docks and maintained them. The shipwright was a skilled worker with the highest being the master shipwright. In addition there was a diverse range of jobs such as sawyers, coopers and rope makers. Particularly prior to the 19th century there were a lot of women employed in the Dockyards. Later when steel was used for shipbuilding the skills needed changed and for example riveters and welders were needed and moving into the 20th century there was an increase in office staff. The workers also needed to be fed involving contracts with local suppliers.

A world of their own

in many respects the dockyards were a world of their own; high walls and gates meant they became insular and hierarchies developed. The principle officers lived within the walls of the dockyard and those of a lower level lived in local communities. A mind set developed that the dockyard and employees were different to the outside world. This meant that when the dockyards closed, as well as local unemployment and economic depression, there was often a sense of dislocation in the community.

A national institution

Before the railways the Navy was one of the few institutions where large numbers of people from all over the country came together. For example during the 17th century many men moved from Tyneside to Deptford, Woolwich and Chatham. A good example of this is at Pembroke docks in the 1810/20s where Charles Cozens, born Churston Ferrers, Devon, Richard Tregenna of Millbrook, Cornwall and John Davidson of Gateshead were employed. Also employed at Pembroke but from further afield was Joseph King, aka Joaquin Mendoza of Portugal, boatswain, who was recommended by Nelson following service with him at Trafalgar. So it would be worth a family historian who has ‘lost’ an ancestor with an occupation related to ship building to look for them in geographical areas with Naval Dockyards.

Dockyard records

The Navy was meticulous in record keeping but Records Offices have not always been good at indexing them. Pre 1660 very few records survive, they were either destroyed as a matter of policy or perhaps in a fire in 1673.

In 1673 Samuel Pepys became Secretary of the Admiralty and reorganised its paperwork, so many records begin then. Prior to 1832 the Navy was run by Admiralty and Navy Board. In 1832 the Navy Board merged with the Admiralty which resulted in discontinuation of some records and introduction of others. It is worth noting that the workforce was categorised into two groups: ordinary, or the permanent workforce, and extraordinary, those additional workers taken on, for example, in times of war.

Where are the records?

The location of the records depends on the period being searched:

Post-1938: Data Protection Cell (Navy), Victory View, Building 1/152, HM Naval Base, Portsmouth, PO1 3PX

1928-1938: The Directorate of Personnel Support (Navy), Navy Search, TNT Archive Services,Tetron Point, William Nadin Way, Swadlincote, Derbyshire,DE11 0BB. Tel: 01283 227913

Pre-1928: Principally The National Archives, Kew – go to www.nationalarchives.gov.uk > Records > In-depth research guides > Royal Naval dockyards

Pre-1928, at the National Archives:

(Note: these are taken directly from Dr Davis’ slides)

ADM 7 Muster Books, Salaries & Pension Books 1694-1832, Salary Books 1709-1879, Yard Officers and Yard Books, 1806-1833

ADM 36 shows seamen via their ship (ships’ carpenters were apprenticed in dockyards). Start with a year you know your ‘target’ was in and work forwards, backwards. When he moves to another ship it will say which one until he is discharged.

ADM 42 lists by dockyard, year, quarter, men listed by occupation. Start with a year you know your ‘target’ was in and work forwards, backwards.

ADM 106 a marvellous source for correspondence from all the yards from 1660-1832 – eg. Description books: lists of workmen mostly made at the end of a war to decide who to discharge, e.g. 1748 (ADM106/2976, transcribed by NDS, 1779 (ADM 106/2980 and ADM 106/2981), and other years which list men alphabetically and by trade, showing place of abode, parish, apprenticeship, description and ability. Incidentally David has seen what he thinks is possibly the only finger print of Samuel Pepys in existence on smudged signature on a document in these records.

ADM 42 Pay Books detail workmen’s presence and rate of pay (see free TNA sheet, no 41). Indices will pinpoint the years to start from and give you the piece number for each year from which you will need to order a document. Each entry will record when he entered, from another yard if that is the case, age at entry, and when left, if for another yard, named, so you can follow them around.

Dockyard employment often ran in families: it was a benefit of working there, a perk, you could pass on the probability of a job to your sons. The more valued workmen often had several jobs (eg warder as well as shipwright), and were the most likely to have apprentices, often their sons/nephews.

Quarterly Extraordinary Paybooks list all the workmen by category: shipwrights, joiners, sawyers etc; their rate of pay and how many days worked per quarter. They sometimes have additional useful information, if the wages are paid to someone else, eg executors, widow or master of an apprentice. Sawyers were usually employed in pairs, and sometimes only the first name is listed. Some workmen are reduced in category in times of retrenchment, so a shipwright might become a joiner.

Quarterly Ordinary Paybooks, which listed the salaried officers, the permanent warrant officers of each ship, ‘shipkeepers’ ‘in ordinary’ (laid up in reserve) and the watchmen and warders.

Coopers and Labourers, 1797-1816, yard unknown, ADM 30/58, ADM 30/59, ADM 30/60, ADM 30/61

Shipwrights, 1800 ADM 30/62

Artificers dismissed, 1784-1811 ADM 106/3006, ADM 106/3007

Caulkers, Coopers and Ropemakers, 1798-1831 ADM 6/197

Officers superannuated, 1801-9 ADM 6/403

Civil Establishment of Admiralty and Navy Board (including yard officers), 1694-1832 ADM 7/809-823

Salaries, home yards, 1808 ADM 7/859

Salaries, home yards, 1822-32 ADM 7/861

Pre 1660

Very few records survivals – possibly destroyed as a matter of policy, possibly casualties of 1673 Navy office fire. Some examples of surviving pay lists:

SPD James I cxxxvi quarter book Chatham Ordinary 1622

SP 46/86 part 1 all dockyards, 1645-6

Otherwise it’s a case of working through microfilms of State Papers (Domestic) at TNA

Other sources of records for major yards:

National Maritime Museum – start with research guide B5, Royal Naval Dockyards

Portsmouth Dockyard Historical Trust – www.portsmouthdockyard.org.uk

Chatham Dockyard Historical Society – www.dockmus.btck.co.uk/

Plymouth Naval Base Museum & the Friends www.plymouthnavalmuseum.com/

NB picture for overseas yards is very patchy – Bermuda, Malta, Simonstown good, others less so

Naval Dockyards Society

Books and other general sources:

NDS List of Workmen and Apprentices in His Majesty’s Dockyards in 1748 @ £10.00 plus £1.75 p&p

Bruno Pappalardo, Tracing your naval ancestors (Public Record Office Readers’ Guide, XXIV, 2003) –

Bruno Pappalardo, Using navy records (Public Record Office Pocket Guides to Family History, 2001) –

N A M Rodger, Naval Records for Genealogists (Public Record Office/HMSO, 1988) (later editions)

Naval Biographical Database People, Places, Ships, Organisations and Events associated with the Royal Navy since 1660. Compiled by Chris Donnithorne – www.navylist.org/

Reporter: Rosemary Bailey