By Elizabeth Mills

This article was published in the April 2019 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

William Sewell (1801-1872) was born in Shap, Westmoreland, the third child of Thomas Sewell and his wife, Mary née Close. They both died before his 5th birthday, and he was brought up by his maternal grandparents, John and Jane Close When he was 22 in 1823 he left England for Jamaica. He was employed on a sugar plantation in St Ann Parish. He appears to have been hard working, and certainly managed to save. However, he met, and fell for, a slave girl of mixed race, Mary McCrea. They had a family of three – Elizabeth 1830, William 1835 and Henry 1838 – but never married.

William was very canny because at the time of the emancipation of the slaves in 1838, while working at Knockalva Estate in Hanover Parish, he managed to persuade a couple of plantation owners to part with their estates at a knock-down price. He told them they wouldn’t be able to continue to operate a going concern without slave labour. Of course he was wrong, and made a considerable fortune. He went on to become a leading member of society in Trelawny Parish, as Custos (magistrate) of the area, a Director of Falmouth Water Company, Captain in the Militia, and a JP.

As far as the children were concerned, William died young, and Elizabeth as a mixed race girl married into another leading mixed race family in Jamaica, the Thompsons. But Henry showed promise (he was light skinned enough to ‘pass’ as white) and when he was 13 he was sent back to England for his education. Green Row Academy near Carlisle was his home until he was 18 and went to Glasgow University to study engineering. While at school he rarely went back to Jamaica, and spent the school holidays with a friend, John Crowther, and his large family.

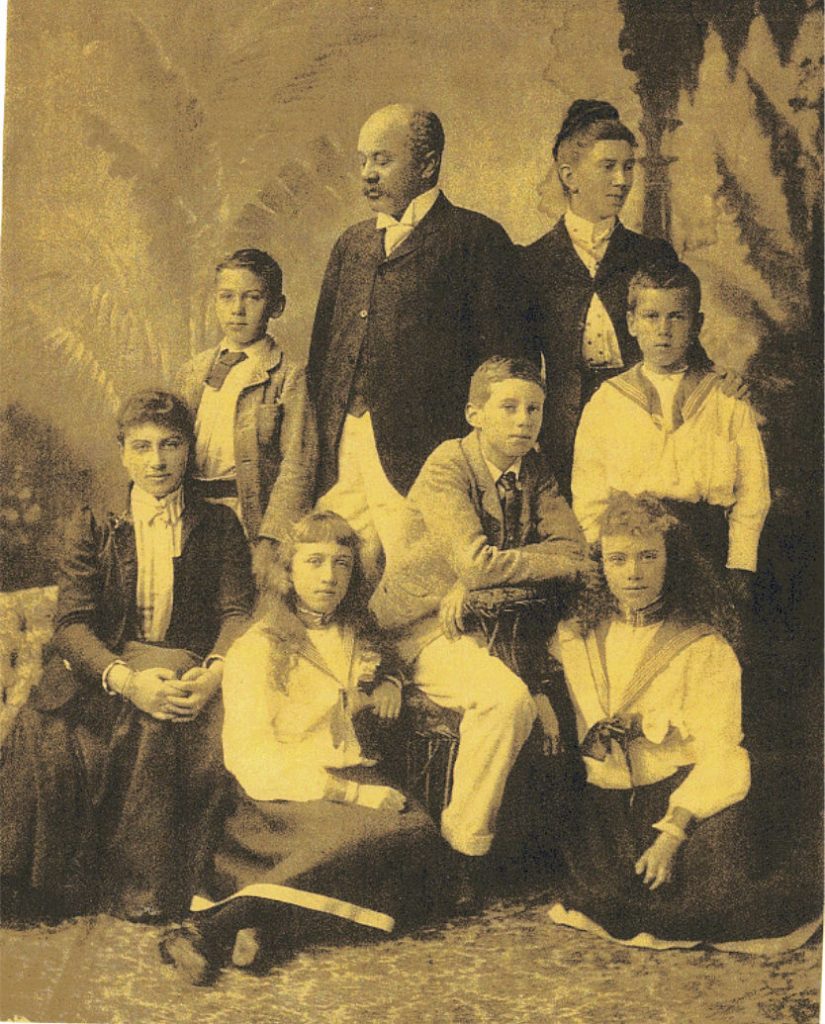

In 1868 William sent for Henry to return to Jamaica to take over running the estates. William’s health was failing. He told Henry that he must first marry a nice white girl to bring back with him. So he returned to the Crowther family, and picked John’s oldest unmarried sister, Margaret, who had always had a soft spot for Henry. They married at Carlisle in March 1869 and left England for Jamaica. Henry and Maggie went on to have six children – Alice Maud Mary 1870 (my great grandmother), Harry Percy 1875, Beatrice Noeline 1876, Arthur Victor William 1878, Elizabeth Anesta 1879 and Horace Somerville 1881.

Sadly, Henry was as spendthrift as his father was frugal, and although his father’s will had set up a trust into which he placed all his assets, with the beneficiaries to be his grandchildren (most of whom were not born at the time of his death in 1872), Henry worked out a way of breaking the trust and lived a luxurious life, both in Jamaica at Arcadia Great House in Trelawny, and in England where he bought Steephill Castle on the Isle of Wight. Sadly the money soon ran out and had it not been for his son Horace’s wisdom in marrying an American heiress, thus bailing out the trust, the properties would have been sold. As it was, the family kept Arcadia until the 1960s, although it was not much use to my side of the family, as Alice had married against her parents’ wishes and had been cut off without a penny!

The latest twist of fate mixed with science relates to another of the siblings, Arthur Sewell. He married Rose in 1900, but clearly in secret. Rose produced a daughter, Joan, in 1905, but Arthur flatly denied the child was his. In 1912, Rose divorced Arthur, and he was declared bankrupt. He committed suicide in 1913 at the age of 35. All through their lives Rose, and later Joan, tried to communicate with the rest of the Sewell family, attempting to prove that Joan was Arthur’s child, but to no avail.

In recent years, I have had my family tree publicly accessible on Ancestry.co.uk and about 4 years ago, I noticed that another tree – user name ‘PetalMac’ – linked to Arthur via Joan, who had gone on to marry a Scot, Charles MacPherson. Charles and Joan had a son, Charles ‘Tony’, and daughter Jennifer. PetalMac and I exchanged messages, and I contacted my cousin, Percy Sewell (Horace’s grandson) in great excitement to tell him that I had found some missing cousins. Percy suggested I was a little careful, as he had seen the old correspondence, and thought that PetalMac and I would find we are not related, in fact. I therefore stopped the correspondence.

Coincidentally some months after this, I was walking the dog in East Oxford one afternoon, and came upon a woman and her daughter, who were clearly distressed by the state of the student house into which the girl was meant to be moving. I asked them if I could help. Once reassured that all would be well, we exchanged contact details, and went on our separate ways. We made friends by email over the subsequent months, and I suddenly realised that this was PetalMac aka Fiona Macpherson. We then met at a conference that I ran at St Hugh’s College and had a good talk about the coincidence.

So we decided to have our DNA profiled via Ancestry, and my cousin Percy did the same, as did one of Beatrice’s grandchildren. Fiona even managed to persuade her 87 year old father, Tony, to have his done too. And the results came back that we are cousins, and that Arthur was wrong.

The family party at Percy’s house at the end of September 2018 was a great and fitting celebration. We invited every descendent of Henry and Margaret Sewell, and 40 of us gathered for lunch. Speeches from Percy, from me, and from Tony told the assembled family the whole story. My finishing line – ‘I hope that this party has gone some way to righting a hundred-year-old wrong’ – went down a storm.

How’s that for a genealogy story? The ‘Descendency Chart’ I did for the occasion spread across 4 metres of the special family tree paper and includes 7 generations from top to bottom. All of Henry and Margaret’s children (at least those who married and had children) were represented at the party. And the sun shone.

This article first appeared in the April 2019 edition of the Oxfordshire Family History Society Journal and is reproduced here by kind permission of the author and journal editor.