By Fred Sole

This article was published in the April 2014 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

A further instalment in our President Fred Sole’s early life. He has now left school and is working as an errand boy in a grocers. It is the early 1940s and the contrast between the grocery store and a current supermarket is vast. Rationing was in force due to the Second World War.

Out to Work

When one begins one’s first serious employment, details of pay and the hours of work are invariably the most important figures, so it is with some guilt that I admit I cannot now remember the amount of my first weekly wage as an errand boy (I think it was about five shillings — 25p). What I can remember is that my wages at the end of my apprenticeship were one pound ten shillings (£1.50) per week, Getting the job was the first priority then, everything else was a bonus. I achieved that aim in a few months before leaving school when I began the errand boy job at the grocery shop. This situation was a little unusual because at first I was part-time. I went in after school from about 4.30pm until closing time at 6pm and on Saturdays all day from 8.30am until 6pm — less an hour for lunch between 12 and 2pm depending upon deliveries required.

The shop seemed large at the time (especially when the tiled floor had to be washed on Monday mornings!) but by modern standards was quite small. Just inside the double front doors, on the left was the cashiers’s kiosk from where a polished mahogany grocery counter ran almost to the far end of the shop.

On the right side, the provisions counter, which dealt with the customers bacon, cheese, fats and ‘deli’ requirements, ran about two thirds of the shop depth. The cost of each customer’s purchase from each counter was entered on a carbon duplicated tear off ticket which was taken to the cash desk where the cashier dealt with all the payments. I suspect the need to be able to calculate the cost of the items that made up a week’s groceries for a large family, in spite of the restrictions imposed by rationing, would horrify most school leavers today – at 16 never mind 14!

The rear of the public area of the shop led to a narrow area across the width of the premises. This contained the Manageress’s ’stand-up’ desk, a wall telephone, a gas ring and a recess for staff coats etc. and shop laundry. Further back still was the ground floor warehouse and last of all the bicycle and tricyle shed and staff toilet (ONE).

Quite a lot of the ’dry’ goods sold then were not pre-packed (tea was an exception) but arrived at the shop in large jute sacks which had to be ’weighed up’ into quantities suitable for the various ration allowances that were in force. Weights and measures were imperial of course, and money was reckoned in non-decimal £. s. d. (pounds, shillings and pence).

Butter, margarine, lard and ’cooking fat’ (a low grade animal/vegetable fat) all arrived in large quantities – usually 28 pounds (15kg) that had to be broken down for resale. Bacon was delivered either as whole sides of a pig and occasionally separate hams, both smoked and unsmoked (’plain’ or ’green’) which had to be boned and jointed before slicing. Cheeses were whole weighing about 30 pounds (15kg) covered with a fine muslin skin which had to be removed – a job I hated. A few processed cheeses were available off ration, but were disliked by older and ‘country’ customers. Deliveries came in every two weeks and immediately afterwards a frenzy of weighing up the dried goods commenced. I was expected to join in and soon discovered how much sugar on the scoop would equate to 8 ounces (0.25kg) in one of the small blue paper bags that identified the product on the shelves. Other amounts of the same product were packed in the same way in larger bags of the same colour.

Other products, rice, dried beans etc. were dealt with in much the same way. The provision fats were also broken down into multiples of the ration allowances but only one or two blocks at a time due to our limited storage facilities. We were also able to grind fresh coffee beans for customers but it wasn’t highly popular. The smell in shops that still offer this facility always takes me back to my grocery years.

During the summer months the shop’s lack of cold storage facilities made it necessary for the bacon to be protected from marauding insects by liberally covering the cut and ‘boned’ surfaces with pepper and fine muslin. There was no danger of visits by officials pursuing such nonsense as ‘Health and Safety’! We were fortunate that a local agreement had been reached with the butcher shop two shops away to store our bulk fats in his very large refrigerator. In return we allowed him to use our bacon slicing machine because he didn’t possess one.

Food rationing was in force all the time I was at the shop and customers had to be registered with a particular trader for rationed goods and if they had them delivered it was usually on the same day every week. Sometimes a local taxi was used for multiple deliveries in the Kings Dyke and Coates areas but the errand boy or another member of staff had to accompany the orders.

After a few months my apprenticeship was approved although I continued as errand boy for a week or two until my replacement was found and briefed on his duties.

The new errand boy was a school friend, Norman Jones, who joined me later in the Army Cadets and in my early musical days. The other staff members I can remember from that time were Geoff Bedford, Fred Smith and Peter Cowling on the provision counter and Joan Blow (later to become Mrs Kisby), Mrs Connie Coulson, Joyce Hipwell (later to become Mrs Rudd), and Marjorie Tysome (later to become Mrs Smith) on grocery. Our cashier was Renee Gobby and the manageress was Mrs Long.

Within a few months Geoff Bedford and Fred Smith had left for the armed forces and the grocery girls shared the provision duties with Peter Cowling. Later members of staff were Beattie Willmer, Irene Shaw and Mrs Dorothy Pickett and both Renee Gobby and Mrs Long left and were replaced by Ida Stalham (later to become Mrs Birch) and Mrs Nutt respectively.

The shop was visited at regular intervals by our Area Inspector Mr Strouts who checked on the work procedures and observed staff attitudes towards customers.

During an apprentice’s time Mr Stouts would also play the part of a customer, with a substantial order and at the end ask for it to be packed for him to take away. The idea was to see if the apprentice had learned how to make up a parcel of grocery items with brown paper and string so that it did not sag or fall apart when carried. Not a simple task, especially when he seemed to have a liking for difficult items like large pots of jam, biscuits (which were almost always sold loose from large tins) and canned items. We seldom had cardboard boxes and they would not have been allowed during the test anyway. To this day I have no problems with packing things for the post.

After about a year I joined Peter Cowling on the provision counter and found my way around all the requirements of that side of the business. When Peter left to join the RAF a new apprentice arrived – Eddie Lemmon. He was younger than me and Norman of course, but we know him from school days.

Some six months later, after my 17th birthday (1944), I volunteered for army service. Initially I had thought of making that a career but the recruitment officer recommended that I go for ‘Duration of the Emergency’. He explained that I could not be called until I reached 17½ but he could arange the necessary paperwork and medical tests in advance. If I was accepted I would have a choice of regiment in which to serve and if I found myself suited I could then ‘sign on’ and all my service would count.

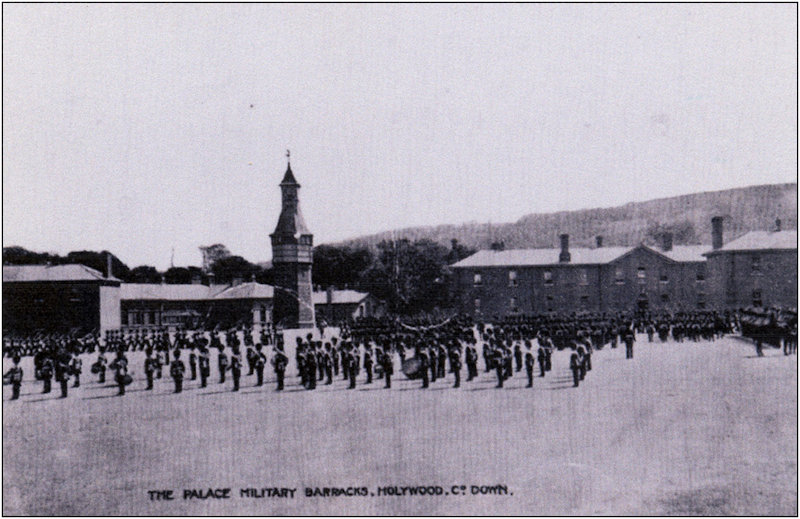

I was given a choice of joining date, so I opeted to have Christmas 1944 and New Year’s Day 1945 at home. True to their word, on 2nd January I was on my way to ‘C’Company of the 28th Training Battalian at Palace Barracks in Holywood, county Down, Northern Ireland.

To be continued…