By Fred Sole

This article was published in the December 2013 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

We continue with Fred Sole’s memories of his early life covering his school days during the thirties and early forties. By then Fred was living with his grandma and Aunt Blanche in Whittlesey, Cambridgeshire.

Reading Marking and Learning

Schooldays from five to eleven were, to me, frustratingly pointless. My efforts to understand what the teachers were trying to convey appeared never to be appreciated and I almost convinced myself that I was as devoid of intelligence as they seemed to think.

Not that basic learning was ever a problem as I lapped up times tables, basic arithmetic (written and mental), writing and reading greedily but my ‘why’, ‘how’ and ‘when’ questions seldom seemed to be treated seriously.

Until… at the age of 11 it was time to sit the ‘eleven plus’ examination, known then as ‘the scholarship’. To do this we had to travel to March (11 miles away) by train. Boys who were successful in the test were eligible to attend the March Grammar School and successful girls could attend the March Girls’ High School. Failures would complete their education at the local Senior Boys’ or Girls’ (Elementary) schools.

When the results were announced, exceptionally, three boys were required to sit a second test. One of them was me and another was my friend Roy. None of us knew why and if the teachers knew we were not told. After the second attempt only one was successful and it was neither me nor Roy. We two failures were obviously disappointed but were obliged to accept our misfortune.

Our new school consisted of four classes in the same building in Station Road, Whittlesey. The headmaster, Mr Bertram Walker had a fearsome reputation. He certainly had no hesitation in using the cane in serious cases of default, but by the end of my time I thought it was simply a case of determination to maintain discipline. In later life I convinced myself that we had all misunderstood and underestimated him.

Class 1 consisted (usually) of the new yearly intake and was the responsibility of Mr (Freddie) Platt. Class 2 was under the guidance of Miss Speechley, a small, motherly, unmarried lady whose teaching was impeccable and her authority was unquestioned. A few of our intake were allocated to class 2 including Roy and me – once again we never knew why. During the first week she said to me “Can you see the blackboard?” “Yes miss”, I replied “ but I can’t see what you’ve written on it”. “Ha! – just as I thought. You had better come and sit here in the front. You “(to that seat’s occupant) “take his seat at the back there”. School suddenly became much easier!

Soon after, Granny, who had by now become my legal guardian, ( thereby obtaining the princely sum of 5 shillings (25p) per week for my care!) received a letter from the County Council Office at March asking me to attend for a sight test as I was considered to be in need of glasses. If they proved to be necessary they would be provided free of charge whilst I remained at school. They were proved necessary, they arrived, and brought with them a new world of clarity. I think I know who had been responsible for that!

One year with Miss Speechley was enough to convince our teacher that both Roy and me were capable of the work in Class 4 so that is where we went and we stayed there until our schooling ended. In Class 4 we worked under Mrs (Emma) Walker, the headmaster’s wife, another long term teacher. To me she was another great encouragement.

Class 3 was supervised by Mr Foot whose principal claim to fame was that he owned a Fiat 500 car, one of the original ‘bubble’ cars. That made him envied by all the boys. His arrival each morning was heralded by the (eagerly awaited) sound of an approaching mechanical disaster. Mr Foot was also an enthusiastic sportsman and it was unfortunate that the school had no sports periods on its timetable. The more ‘active’ boys were thereby denied an opportunity for physical competition and that must have contributed towards the occasional classroom outbursts.

Mr Walker took classes if a teacher was away for any reason and also performed some duties for St Mary’s church (as ours was a ‘church’ School) which was a couple of hundred metres away on the opposite side of the road. He was also an accomplished pianist and accompanist.

Fred is second from the right in the front row, Mr Walker the

headmaster is last on the right in the second row from the back

On Saturday mornings (and other mornings in holidays) he expected the school captain and a class monitor to attend his house and do light jobs and errands for which he always paid sixpence ( 2½ p in today’s money).

His unmarried sister Enid, who was headmistress of the Girls’ Senior school in West End, lived in Whitmore Street and doing similar jobs there was part of the assignment. As he kept his car at Whitmore Street car washing was sometimes required too. Slave labour ? … Possibly, but we wanted the sixpences!

During and after the summer holidays while the country was at war older boys were allowed to help farmers with the potato harvest. The headmaster had to be satisfied that the boys’ educations would not be jeopardised and the farmer had to confirm the employment.

I was taken on as a ‘Cart Boy and Catcher’ by Mr Herbert Butcher who farmed in the Thorney Fen/Northside area, a couple of miles north of Whittlesey. The job entailed standing in a tumbril cart as the horse made its way up and down the lines of wicker baskets (skips or skeps) that had been filled by the women potato pickers after the ‘spinner’ had unearthed them.

An experienced (and fit) farmhand walked alongside the cart, holding on to a stay at its rear and, without a break in his rhythm, swung each basket up to the catcher. The catcher caught the basket as it was upside down so that the potatoes fell into the cart and then threw the basket over the other side of the cart so that it was ready for the next round of the spinner and pickers.

When the sequence was going well it was all too easy for the catcher to forget to reposition his feet frequently, and to find it almost impossible to lift them out of the potato pile. Woe betide you if the cart had to be stopped to get you out of the predicament. Even the horse would look put out!!!

When the cart was full the catcher had to lead the horse to the ‘grave’ where the potatoes were to be stored, which might be in the field or nearer the farm house or, more often, beside the nearest roadway. There he would wait for the cart to be emptied, or take a waiting horse and empty cart back to the field to repeat the cycle.

The work could be tiring for a 13 year old but at the end of a day it was very satisfying to see all the dead haulm (tops) cleared away and usually burnt on site – a wonderful way to get a large (free) roasted potato for ‘dockey’ (lunch) – and the levelled ground ready for winter ploughing..

The early morning starts were difficult too at first, but luckily Aunt Blanche was one of our pickers and she made sure I was ready for the gang master’s wagon when it arrived in the street at about 6 am. With my dockey bag containing some sandwiches and a bottle of drink I felt quite the workman. One or two others from school were also on the field which made it easier. For the outward trip my overcoat was a necessity. Half an hour or so on an open flat wagon, behind a steadily plodding horse on a chilly morning, soon proved that point.

During the six weeks or so that I ‘lived off the land’ I took my first step into the world of industrial relations, albeit in a very small way. Our boss Mr Butcher was, I think, one of four brothers who farmed in the area and all of them employed schoolboys in the same way. However, someone on our farm had heard that boys working for one of the other brothers were receiving three shillings (15p) per day, whereas we were only getting two shillings and sixpence (12 ½ p).

After a couple of weeks listening to this story I decided to ask Mr Butcher if this was true, so I spoke to him when he was next on the field. He said he didn’t know, but he would find out. If it was, for my b….. cheek we would get the same from next pay day. It was, and we did! Similar attempts in future employment – not always about money – were often more difficult but, although I won a few more, none were quite as satisfying.

Many years later I was to visit an aged Mr Butcher in response to a problem reported with his telephone service in his retirement bungalow. Then a Sales Rep, I didn’t normally get involved with residential customers, but my sales clerk thought it advisable in his case. He lived in my area so it was my problem. The incident I had completely forgotten, but the name brought it all back. When Mrs Butcher showed me into the room where he was seated the years fell away. With a solution to his problem decided upon, we enjoyed our inevitable cups of tea and I asked him if he remembered the incident. “Until today, no”, he said “but it was my brother I told off for not telling the rest of us what he was up to!”. A ‘Gentleman Farmer’, I think.

Much as I enjoyed those few weeks on the land I knew I didn’t want to be there permanently when it became time to leave school, but deciding upon an alternative was not easy. I was helped by Mr Walker, the headmaster, who told me that the manageress of the local branch of the International Tea Company grocery store (where he bought his goods) needed an errand boy. He advised me to consider it because it would be likely to lead to an apprenticeship to the trade, and that would make an excellent start to a good career. As the only qualification for the post was the ability to read and write and ride a bicycle I happily accepted the chance.

I soon found out, of course, that riding a heavily laden trade bicycle was rather different from my expectations, but perseverance solved that problem. I even achieved mastery of the box tricycle that had to be used occasionally, and discovered it could be a source of fun – when it was empty!

Long after school when I was seeking different employment I was obliged to undergo an aptitude test. The test was used nationally by my prospective employer and afterwards I was told my results were exceptional – well over 90% without answering two questions because poor duplicating had

rendered the questions unreadable and consultation with the supervision was barred.

Later on I sat another exam for promotion within the same organisation. It was much more daunting, covering Numeracy, Vocabulary, Literary ability, General Knowledge and interview capability. My final position in the results list of successful candidates of 5th out of 350 applicants was, I thought, quite creditable. It also confirmed how much was due to my later schooling, because, in the written part of the exam I came equal second. With many of the applicants being ex-grammar school I was well pleased.

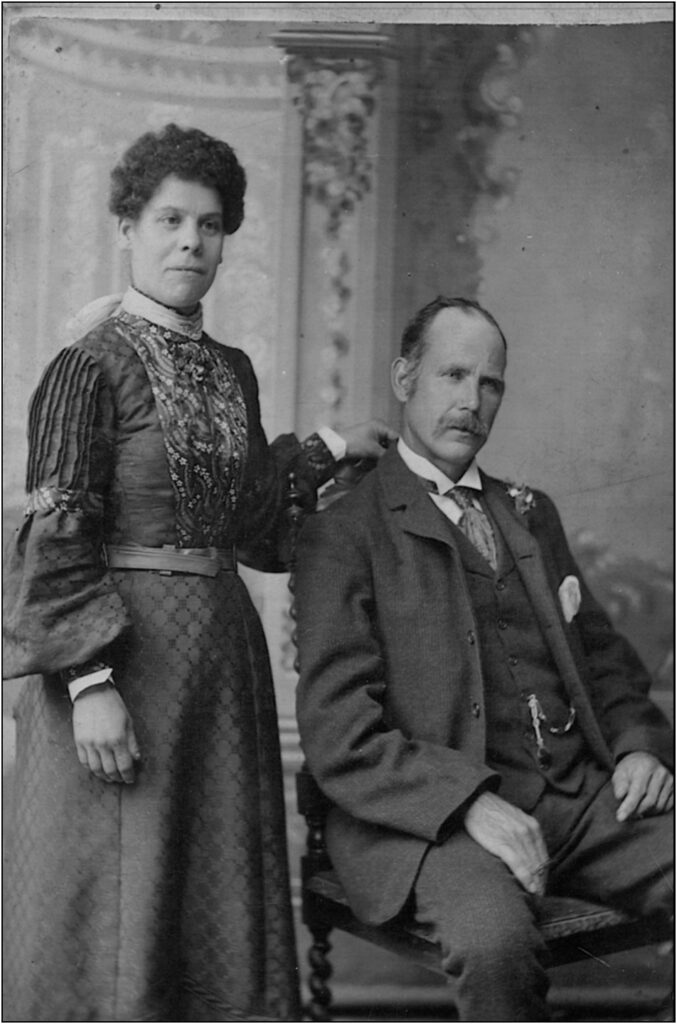

On page 31 of the August edition of the journal the picture captioned Fred’s grandfather, John OVERALL should have read Fred’s grandfather Alfred Sole. A picture of John Overall with his new wife is shown bellow. Apologies to Fred and his grandfathers!