By Maureen Storey

This article was published in the August 2014 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

Arthur Frederick Soole was born in Seaforth, Ontario, on 17 November 1890. He was the son of Charles and Margaret (née Love) Soole and the grandson of George Soole, who had emigrated from Ickleton, Cambridge, to Canada in 1857. In about 1911 Charles and his family moved to Winnipeg, where Arthur found work as a clerk for a company dealing in dry goods. Like many young Canadians, Arthur answered the call to arms to aid the Home Country during the First World War and on 11 March 1916 he enlisted in the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force. After his initial training he was sent to England, landing on 11 November 1916. On arrival he was transferred to the 27th Battalion, and he joined the battalion in France on 29 November. On 21 April 1917 during the Battle of Vimy Ridge he was seriously injured with gunshot wounds to the face and arm and was transferred back to England.

To those of us whose experience of gunshot wounds is limited to what we see in films and on television, a gunshot wound that hits no major organ seems relatively trivial (though painful) – just a neat little round hole where the bullet enters and, if the bullet passes through the body, a slightly larger exit hole. Reality is very different as can be seen only too graphically when soldiers receive gunshots to the face. Often large areas of the face are destroyed, leaving the soldier with a gaping hole where his mouth, nose or cheek once was. The gunshot to Arthur’s face, as well as damaging his jaw bone, destroyed much of the soft tissue below his mouth. He was sent to Queen Mary’s Hospital in Sidcup, Kent, where he received treatment from the team led by pioneering plastic surgeon Harold Gillies.

Harold Gillies was born in New Zealand in 1882. He studied medicine at Cambridge University and qualified as a surgeon. He joined the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1915 and for a while worked in Wimereux with the American–French dentist Charles Valladier, who was developing techniques for replacing jaws that had been destroyed by gunshot wounds. He also met Hippolyte Morestin, who was working on the use of skin grafts.

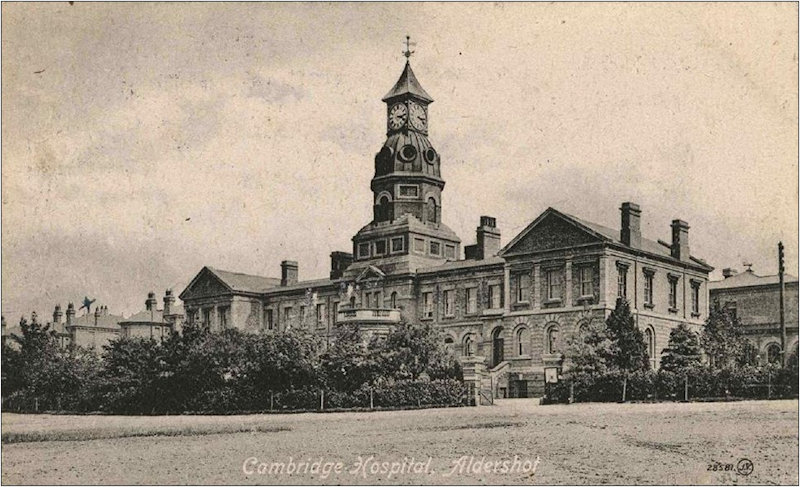

Gillies persuaded the Army to open a ward at the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot specifically for the treatment of facial wounds. In June 1917 his unit moved to the newly opened Queen’s Hospital (later Queen Mary’s Hospital), Sidcup, and between then and 1925 Gillies and his colleagues operated on more than 5000 men (mostly soldiers with gunshot injuries, though there were also a number of burns cases).

Many of the wounds Gillies treated were quite literally flesh wounds. Provided the soldier survived the initial loss of blood and did not succumb to infection, these wounds were often not life threatening but they were most certainly life changing. Previously very little had been done other than sewing up the wound, leaving the soldier with horrific scars. Missing noses were replaced with flesh coloured metal prostheses held in place with spectacle frames. Some men were given masks to hide the scars, but many could not face the outside world, or even their families, and spent the rest of their lives hidden away in institutions. Gillies was one of a new breed of surgeon who focused on aesthetics: his aim was to make his patients look similar to how they were before the injury.

Gillies developed a technique using ‘tubed pedicles’ to replace missing parts. In this technique a flap of healthy flesh from another part of the patient’s body was stitched to the wound. To keep the flap alive while the graft took, it was left attached at one end, for example, a pedicle might run from the patient’s chest to his jaw. Once the graft had taken, the pedicle would then be detached from the chest and the repair completed. Large skin grafts were difficult and despite the surgeons’ best efforts did not always take (as was the case in Arthur’s first operation in Sidcup), so repeat operations, building the repair a little at a time, were often necessary. The process was a very protracted one, often spread over years, but the end result was usually that the soldier was left with a face with which he could face the world.

Gillies used photographs and drawings taken before and after each operation to track the patient’s progress. The drawings, which were usually done in pastels, were produced by or under the supervision of Henry Tonks, the Slade Professor of Fine Art. Tonks had originally trained as a surgeon and taught anatomy at the London Hospital Medical School. He gradually turned from medicine to art and by 1892 was teaching at the Slade School of Art. With the outbreak of war he returned to medicine. By 1916 he was a lieutenant in the Royal Army Medical Corps and started working with Gillies.

Nowadays Gillies is regarded as one of the fathers of modern plastic surgery but during the war his efforts went largely unnoticed (except by his patients and their families). His achievements were not really recognised until 1924 when he went to Copenhagen to treat some Danish naval officers and men who had been burned in an accident. Gillies was knighted for his war services in 1930.

After a series of operations, Arthur Soole decided to return to Winnipeg. He was scheduled for more surgery but obviously decided that enough was enough. The end result was not perfect but it was one he could live with. One of the side effects of his injury was that he was very susceptible to the cold and so in about 1920 he moved from Winnipeg to Vancouver, where he started a grocery shop in Victoria Street. He married Ruby Johnson in 1929 and the couple had one daughter, Eleanor Margaret. Arthur died in Vancouver in 1972.

Many of the notes (and accompanying pictures) for men treated for facial injuries during World War I have been preserved in the Harold Gillies Archive at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup, Kent. Other men of interest to the Sole Society to be found within this archive are:

Private Arthur Sewell of the Sherwood Foresters, born 1877, wounded 14 February 1916, gunshot wound to face, fractured mandible.

Private Horace Sewell of the North Irish Horse, wounded 1 January 1914, nose.

Private Robert William Sewell of the Royal Army Medical Corps, born 1888, wounded 1 July 1916, gunshot wound face, fractured mandible.

Gunner Thomas H Sole of the Royal Field Artillery, born 1889, wounded 23 August 1914, gunshot wound face, fractured mandible.

Postscript: After the war Gillies developed a substantial private plastic surgery practice. In 1930 he invited his young cousin, another New Zealander, who had become interested in plastic surgery, to join the practice. This cousin was Archibald McIndoe, whose pioneering treatment was to have a profound effect on the lives of many of the young airmen who suffered severe burns during the Second World War.