Heroism or High Mindedness?

By Peregrine Solly

This article was published in the August 2021 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

Dan Re’em’s request for information about Edward Solly (Sole Society April 2021) reminded me that I had recently been sent by a note by my brother telling me about an impressive ceremonial sabre that was sold by Bonhams in 2015. The sabre had been presented by Edward Solly to a British Army officer following the Battle of Leipzig which Edward had attended as an observer. Edward is gaining fame as one of England’s most remarkable picture collectors; however, I wondered if Dan knew that Edward had another altogether more adventurous side to him. Edward not only attended the battle of Leipzig, but then volunteered to bring the vital news of Napoleon’s defeat back to London, travelling through enemy territory at great risk.

I already knew something about Edward’s Leipzig adventures as they are mentioned in Frank Hermann’s profile of him in the Connoisseur Magazine which was published in 1965. Hermann notes that Edward managed to get back to London 24 hours ahead of the King’s Messenger, but that “after a heated debate with his brothers” the Sollys decided not to make a financial killing by releasing the wrong news and crashing London’s financial markets. This, Hermann notes, was unlike Nathan Rothschild who also reached London ahead of the official messenger with the news from the Battle of Waterloo. However, the Rothschild’s were apparently less high-minded than the Sollys and, as the story has it, they made a fortune by announcing that Waterloo was a victory for Napoleon. Edward’s honesty was both a source of pride and disappointment to us as children as we would not have minded knowing that the Sollys could have rivalled the Rothschilds in wealth and financial acumen. Ironically, I now believe we had no reason to be disappointed, as there is no evidence that either the Sollys or the Rothschilds tried to capitalise on their news.

The sabre is magnificent and was sold at auction in London for £43,750 in 2015, an impressive price for a sword. However, it is not just proof of Edward’s connection with Leipzig but it links him with two of the more colourful military figures of the time: Thomas Noel Harris who was to become one of the heroes of Waterloo and was twice knighted, and Charles (Vane) Stewart (later the Third Marquis of Londonderry) who was popularly known as “Fighting Charlie”, but was also mocked in court circles as “Lord Pumpernickel” for his boorish behaviour.

In 1813 Edward Solly was 37 and had moved to Berlin from Stockholm. Edward was the Baltic agent for his family’s business, Isaac Solly and Sons, which was the main supplier of hemp and timber from Northern Europe to both the Royal Dockyards and to the Prussian Navy. It was the time of the Napoleonic Wars, and the business was highly successful, with Edward using his considerable wealth to amass an outstanding collection of Italian and Dutch Old Masters.

It was also the year when Lieutenant General Sir Charles William Stuart, who was two years younger than Edward, arrived in Berlin as the British Envoy to the Prussian Court. Charles Stewart had gained a reputation as a dashing cavalry officer during the Peninsular Campaign under Moore, but then had been made Adjutant General by Wellington. This was an administrative role to which Stewart was completely unsuited and he was soon sacked by Wellington. Fortunately, Stewart’s brother was Lord Castlereagh, the Foreign Secretary, and he was quickly launched on a new diplomatic career and sent to Berlin as the Envoy to the Prussian court. Stewart was also given the role as the senior British liaison officer to a new military coalition of Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Sweden that was being put together to defeat Napoleon.

Edward Solly and Charles Stewart will have moved in the same circles in Berlin, and Charles may well have found Edward’s knowledge of northern Europe useful. Whatever the reason, Charles invited Edward to join his entourage in October that year to witness “The Battle of Nations” at which the coalition was hoping to deliver a crushing blow to Napoleon whose ‘Grande Armee’ had been largely destroyed by his Russian campaign the year before. The Battle of Leipzig, as it normally known, has the distinction of being the largest battle fought in Europe before the World Wars and was a long and bloody affair involving over 600,000 troops – 50,000 of whom were killed.

The sabre is dedicated: ‘From Edward Solly To Thomas Noel Harris, In Commemoration Of Their Fellowship At The Memorable Battle Of Leipzig Of The 18th And 19th Of October 1813’. These were the last days of the battle which began two days earlier on 16th October. Captain Harris (1783-1860) had been with Charles Stewart in the Peninsula Campaign and came with him to Prussia as his ADC. At the time of the battle, Harris was attached to the Prussian Cavalry under General Blucher, and it may be the Prussian connection that linked him to Edward. Whatever the link, the sabre is a gift of great generosity and I suspect that Captain Harris may have done more than just keep Edward out of trouble. I have nothing definite to support this idea, but in his memoirs, Charles Stewart does complement Thomas Harris for his efficiency and gallantry, and he also says that Harris alerted Blucher to the presence of a column of 5,000 French soldiers that were closing in on the Prussians; a discovery that may well have been critical to the course of the battle. Harris was normally in the thick of any action. He was later to survive Quatre Bras and Waterloo, despite having two horses shot from under him, getting shot in the chest and losing an arm. Amazingly he lived to a good age and became quite a hero, being knighted twice and becoming a favourite of Queen Victoria’s. His bloodied coat from Waterloo is one of the more gruesome exhibits at the National Army Museum.

Edward’s heroic mission after the battle was later written up by his son and published in 1884 [Note 1]. Charles Stewart needed get the news of Napoleon’s crushing defeat back to London to his brother-in-law, Lord Castlereagh the Foreign Secretary, as fast as possible. The plan was to send one of his ADCs, a Lieutenant Jones, with his despatch who would travel via Hamburg to the Baltic Coast as this was largely through coalition-held territory. Edward however volunteered to get the news to London faster by travelling through Holland although this was enemy territory. As his son puts it: ‘Blessed with good health and untiring energy and provided with an Englishman’s key – a well-stocked purse – he set out on his journey.’ The journey took Edward fifteen fraught days and he eventually arrived in London on the evening of 2nd November with news of the victory twenty-four hours ahead of Lt Jones. Proving the value of having his “purse” with him, Edward was able to sail to England across the North Sea on board a Dutch herring boat ‘having paid the fishermen more for his passage than the entire value of the boat and all its paraphernalia’.

According to his son’s account, Edward went straight to Lord Castlereagh’s home and gave him General Stewart’s dispatch. In Frank Hermann’s version, Edward went first to the family offices where there was an intense debate about whether the brothers should use the opportunity to their considerable financial advantage by releasing the news that Napoleon had won and then buying-up stock as the market crashed. His story is that the Solly’s were high-minded non-Conformists who did the honourable thing, releasing the true news; unlike the Rothschilds who made a fortune by ‘spooking’ the London market with the wrong result of Waterloo [Note 3]. As far as I can tell, neither story is true. Edward’s son’s account is very detailed, explaining that his father was momentarily panicked while waiting for Castlereagh, as there was another muddied traveller in the anteroom who Edward thought had beaten him with the news from Leipzig; there is no mention of the earlier family argument. Equally, the Rothschilds were not the first with the news from Waterloo, and there is no evidence that they made a fortune with the news; the current view is that this story was a bit of malicious journalism, possibly anti-Semitic in intent.

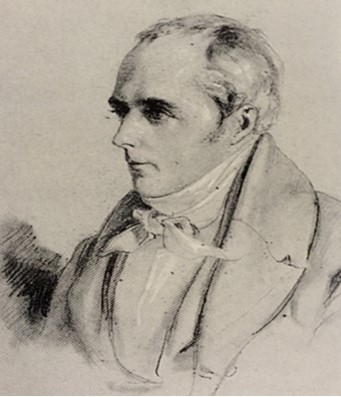

It is easy to think of Edward Solly as simply a great collector and connoisseur. The most recognised portrait of him on page 24 shows him looking elegant and aesthetic. Yet, Edward must have had a tough and adventurous side to him to have managed his family’s business as successfully as he did. He was constantly operating far from home, essentially in a war zone. He clearly was able to connect with a range of interesting characters and he was no ‘shrinking violet’, joining Charles Stewart’s entourage to the battle and then volunteering to take the news of the Coalition victory to London. Edward Solly was certainly a remarkable man, both high-minded and a hero.

NOTES:

Note 1: Edward Solly’s sabre: The sabre is exceptionally fine and ornate and came with two scabbards There is a recent description of the sabre in the Bonham’s auction catalogue of its 2015 Waterloo Sale, and an earlier description by D.H. Tomback: ‘The Sword Of Lieutenant Colonel Sir Thomas Noel Harris K.H.’ in the Journal Of The Society For Army Historical Research (Spring 1987), Vol. LXV, No. 261, pp. 20-22.

Note 2: Edward’s journey back to London with the news of the battle was written up by his son, also Edward, in ‘News and Newspapers’, The Bibliographer (March 1884, vol. 5, p. 91) which is available online. The article was making the point about how fast news could travel in the days of the “electric telegraph” and the son used his father’s adventure as example of how difficult it was to get vital news back to England before the advent of electricity and the railways.

Note 3: The Rothschilds and Waterloo. The story that the Rothschild’s made a fortune by spooking the London financial market with the news of the Waterloo had been a victory for Napoleon is very well established; it has been repeated by some serious historians, as well as Frank Hermann, and even made its way into the Encyclopaedia Britannica. It seems to have its origins in an anti-Semitic pamphlet produced in Paris in 1884, although the Duke of Wellington told the story a number of times in the 1820s and 30s. The truth seems to be that Nathan Rothschild did get the news ahead of the official messenger, but so did some others, and the news of the victory was published in the London Gazette some hours before the official announcement was made. However, the Rothschild’s did not make a fortune and the story seems to be more legend than fact – see Brian Cathcart’s 2015 book “The News from Waterloo”.