By Rosemary Bailey

This article was published in the December 2022 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

We were delighted to welcome Dr Judith Hill to speak at our Annual Gathering in October. Her talk was entitled Emigration from Britain towards the end of the 19th century and the age of the ocean liner and we would like to thank her for providing us with an abstract which is reproduced here.

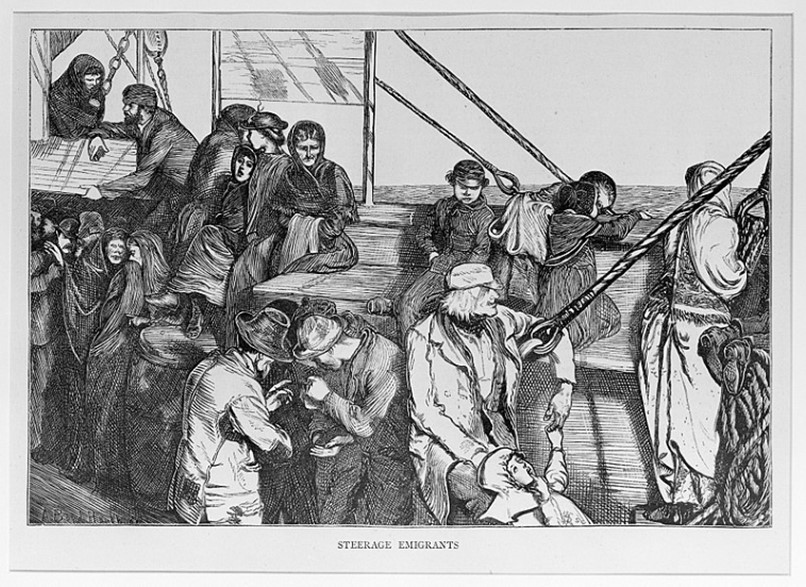

At the beginning of the nineteenth century it was the merchant ships that carried passengers who were emigrating but none of these ships were constructed and fitted primarily for that purpose. The huge demand for North American timber and cotton as raw materials for British industry led to well established transatlantic links. The emigrants along with British manufactured products provide a useful return cargo across the Atlantic. The journey was extremely uncomfortable and hazardous. Sea sickness was a particular problem on the stormy North Atlantic westbound voyage. Most of the early emigrants settled and did not return home. During the first half of the nineteenth century, many British emigrants were farmers, agricultural labourers or skilled artisans and craftsmen from traditional trades; many emigrated in family groups and were from rural areas. This pattern began to change in the second half of the nineteenth century, when many emigrants started coming from urban areas, and young, single, male labourers and agricultural workers predominated.

By the 1850s steam power started to replace sail, iron instead of wood and a screw propeller enhanced the speed and regularity of ocean-going services. On the transatlantic routes voyage time was reduced from a journey on a sailing ship of about 35 days to the US and Canada to 7 to 10 days by steam.

By 1875 with the coming of steam powered ships British emigration rose to new peaks. Continuing progress of technology and the development of steam shipping made emigration more accessible and feasible, reducing the financial and emotional costs at the same time changing popular attitudes in its favour.

From the beginning of the nineteenth century Liverpool was the main port of departure for emigrants from all of northern Europe. Liverpool had developed as an important emigrant port because by 1830 it had established Trans-Atlantic links based largely on the import of cotton and timber and then departing emigrants along with British manufactured products. In 1851 Liverpool had become the leading emigration port in Europe but by the 1860s the other UK ports of Southampton, London and Plymouth were more frequently being used. The development of the railways was also important and by 1881 British railways were carrying 600 million passengers per year to the British ports.

There was an expansion in the middle classes travelling to the USA for business and leisure at the end of the 19th century. At the same time Americans had a desire to visit Europe. The most prominent American voyagers were people like the Astors, Rockefellers, Vanderbilts and Guggenheims, people with enormous fortunes. Shipping companies now wanted to emphasize the splendour, luxury and comfort that travellers would encounter on board. Shipping lines built luxurious liners with first class cabins and public rooms that were comparable to the facilities offered by London’s top hotels. Architects were employed to create exotic interior design schemes for these transatlantic liners – “floating palaces.”