A Naval Life

By Tony Storey

This article was published in the December 2023 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

One of the most distinguished Sewell families we know about must be the descendants of Sir Thomas Sewell, Master of the Rolls until his death in 1784. The May 2006 edition of Soul Search included an excellent article by the late Diana Kennedy, which gives an overview of the family, but I recently discovered some additional information about one of Sir Thomas Sewell’s grandsons.

Sir Thomas’s son, Robert Sewell was baptised in December 1751 at All Hallows, London. He became a Barrister at Law and married Sarah Lewis in November 1775 at Old Street Church, St Pancras. The following February they sailed to Jamaica with Sarah’s sisters who were returning there. In 1780 Robert was appointed Attorney-General of Jamaica.

Robert and Sarah had five children including Henry Frederick, who was born in Jamaica on 19 December 1790. In September 1803 aged 12, Henry entered the Royal Naval Academy at Portsmouth.

In 1801 HMS Phoebe captured the French frigate Africaine a Preneuse class 40-gun frigates of the

French Navy. She carried twenty-eight 18-pounder and twelve 8-pounder guns and had been commissioned in September 1799. In February 1801 she was carrying ordnance, stores and 400 soldiers to resupply Napoleon’s army in Egypt.

The Royal Navy took the former French frigate into service as HMS Africaine, and it became Henry Sewell’s first ship when he was appointed a midshipman aged 16 in March 1807. The ship had been fitted out at Chatham and at Plymouth, and Captain Richard Raggett was in command. On 5 July 1807 she sailed from England carrying General Lord William Cathcart to Swedish Pomerania, where King Gustavus was defending his territory against an invading French army. Cathcart was to take command of the land-forces for the forthcoming siege and bombardment of Copenhagen. HMS Africaine arrived at the island of Rügen on 12 August where she joined Admiral Gambier’s fleet for the assault on Copenhagen. Africaine was in the vanguard and had one man wounded before the Danes capitulated and surrendered their fleet. A prize crew from Africaine took the captured Danish frigate Iris back to England where it was moored in the River Medway, Kent.

By Christmas Eve 1807 HMS Africaine had reached Madeira, where Henry Sewell was able to witness the island’s annexation following the Portuguese garrison‘s surrender. Madeira became a British Crown Colony for just four months as part of a plan to defend the island against Napoleon, while still preserving Portugal’s neutrality. The British occupation was entirely friendly and Madeira was returned to Portugal on 24 April 1808. HMS Africaine then sailed to the Baltic to serve under Vice-Admiral Sir James Saumarez.

In spring 1810 HMS Africaine was in Plymouth, having returned from Annapolis after delivering Mr. Jackson, the British ambassador, to the United States. During this period the crew threatened mutiny when informed that Captain Robert Corbet, who had a reputation for brutality, was to take command. The Navy quickly suppressed any mutiny and the ship sailed for the East Indies with Corbet in command. During the voyage Corbet reportedly failed to train his men in the accurate and efficient use of their cannon, preferring to maintain the order and cleanliness of his ship rather than exercise his gun teams.

In August 1810 a naval battle between frigates from the French and British navies arose over possession of the harbour of Grand Port, Isle de France, (now known as Mauritius). The British squadron of four frigates sought to blockade the harbour to prevent its use by the French and to this end they captured the fortified Isle de la Passe at its entrance. Unfortunately when a French squadron of five frigates arrived, four of the French ships broke the blockade and took shelter in the anchorage protected by reefs and sandbanks. Captain Samuel Pym ordered his four ships to attack the French, but two of them ran aground on sandbanks and could play no part in the battle, another was outgunned and captured by the French frigates and the fourth was confronted by the main French fleet as it tried to retreat. The two grounded ships were set on fire to prevent them falling into French hands. It was the worst defeat suffered by the Royal Navy during the entire Napoleonic War. Worse still, the debacle left the Indian Ocean and its trade convoys at the mercy of the French navy. Urgent messages were despatched to naval bases at Madras and Cape Town requesting immediate reinforcements by all available ships.

Arriving on 11 September, HMS Africaine was one of the first to arrive on the scene. She sent her boats to find a passage through the reef with a view to capturing a French schooner. The boats’ crews succeeded in boarding the vessel, but they had to abandon it in the face of fire from soldiers on shore that killed two men. Sixteen crewmen were injured including Henry Sewell. HMS Africaine then sailed for Isle de Bourbon, which was in British hands, to drop off the more serious casualties. The frigate arrived on 12 September and then sailed that same evening in pursuit of French vessels that had been sighted.

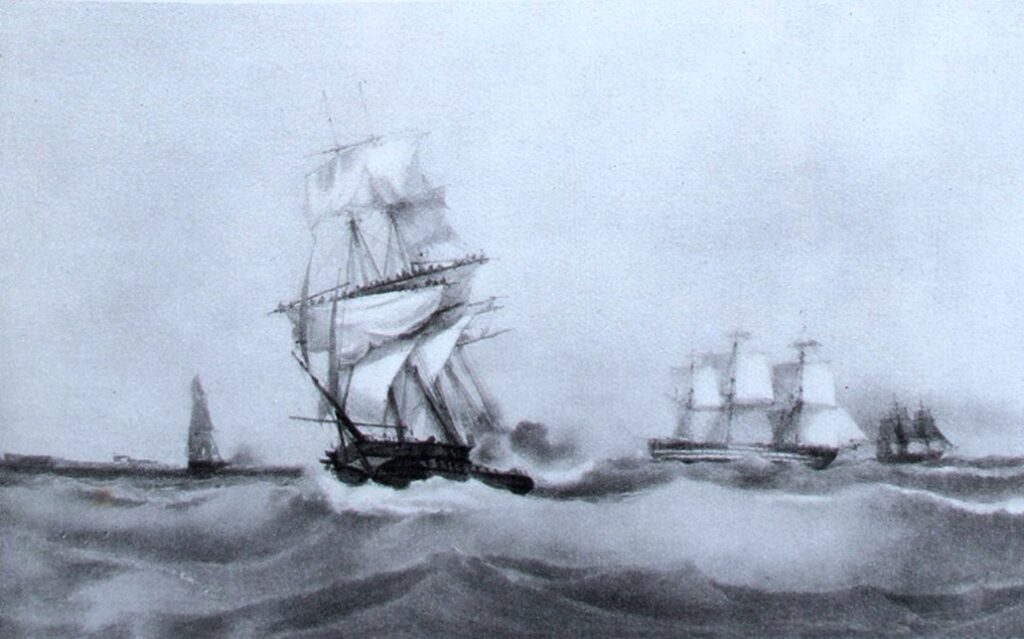

The following day HMS Africaine was captured by two French frigates, Iphigenia and Astrée. When she had chased the French frigates and the brig Entreprenante earlier, she had outdistanced her companions, HMS Boadicea, HMS Otter and HMS Staunch with the result that they were too far behind her to give support. Early in the battle a shot took off Captain Corbett’s foot and his crew took him below decks. HMS Africaine fought on with First Lieutenant Joseph Crew Tullidge having taken command, but after two hours, Tullidge had suffered four wounds and the ship was forced to surrender. The British had captured her from the French in 1801, only to have the French recapture her in 1810. However, the French had to abandon their prize at sea as she had been dismasted and badly damaged. Furthermore, Iphigénie was also sufficiently damaged to require a tow from Astrée. The French lost nine killed and 33 wounded in Iphigénie and one killed and two wounded in Astrée.

HMS Africaine had begun the day with 295 men and boys aboard, including 25 soldiers from the 86th Regiment of Foot. In total, HMS Africaine lost 49 men killed and 114 wounded. In addition the French had taken Lieutenant Tullidge and about 90 crew as prisoners and taken them to Isle de France/Mauritius where they remained until the British took the island in December. When the British recovered her the next day, HMS Africaine still had 70 wounded and 83 uninjured crew aboard, as well as a ten-man French crew.

Corbet died from his wounds, although there were rumours that the unpopular captain had been murdered by his crew. Midshipman Sewell continued to serve in HMS Africaine under the flag of Vice-Admiral Albemarle until December 1810, when he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant and returned to England in HMS Diomede.

In April 1812 First Lieutenant Henry Sewell sailed to South America on HMS Inconstant under the command of Sir Edward Tucker. Between July 1812 and June 1815 Lieutenant Sewell was employed in the Home and Brazilian stations in HMS Diomede, Cornwall, Inconstant, Valiant and Duncan.

After the Emperor Napoleon’s abdication and eventual defeat at Waterloo in 1815 the Royal Navy could afford to put many officers like Henry Sewell on half pay. They could still be recalled to service if the need were to arise.

In November 1819 at the British Embassy in Paris, Henry Sewell married Esther Dawson, the eighth daughter of John Dawson Esq., of Mossley Hill, near Liverpool and the sister-in-law of Vice-Admiral W H B Tremlett. Henry and Esther’s first child, Henry Robert William Frederick, was born in France in 1820. A daughter, Mary Anne, was born in 1825 and another son, John Augustus George Frederick in 1826. A third son, Robert William Dawson, was born in 1835.

In March 1835 Sewell was put in charge of a Coast Guard station. In December that year he captured a smuggling smack, crew and cargo. In November 1840 he was presented with a gold medal from the Royal National Shipwreck Institution for having saved the lives of the crew of the smack Sarah, wrecked on 21 September 1840 on St John’s Point. County Down.

In May 1842 Sewell was having unspecified financial problems and was being pursued by creditors. The situation came to a head in January 1843 when a notice in the Down Recorder requested creditors of Henry Frederick Sewell, an insolvent, to meet at Mrs Foster’s Inn, Downpatrick on Tuesday 31st January at 12 o’clock. Nothing further occurred so it seems the matter was settled.

In October 1846 Henry was commended for using Dennett’s Rockets (right), to save the lives of the 26 passengers and crew of the ship Templeman, wrecked off Kilmore, County Wexford. Lieutenant Henry Sewell left the Coastguard Service in March 1850. He was declared unfit, probably on grounds of age, and retired on half pay. On Census night in April 1851 he was lodging at 14 Greenhythe, Swanscombe, Kent and described as a Lieutenant Royal Navy on half pay. In July 1851 he was promoted to Commander, still on half pay.

By 1855 Commander Henry Sewell was back in charge of the Kilmore coastguard station in County Wexford, Ireland.

Henry’s youngest son Robert William Dawson Sewell also settled in Wexford and in 1855 married Anna Maria Green. Robert was a merchant marine officer and was on board the SS Great Eastern when she suffered an explosion on her maiden voyage in 1859. The Great Eastern was not a commercial success and by 1864 Robert was employed by Sandbach Tinne & Co, as the Captain of their new iron sailing ship, the 835 ton Van Capellan, and he made several voyages between Liverpool, Australia and India. Tragically in March 1865 while sailing from Calcutta across the Indian Ocean the vessel was hit by a sudden squall and capsized. Six of the crew including Captain Robert Sewell were drowned. The sixteen remaining hands managed to launch a small boat, but as they drifted over the next thirteen days their food and water ran out. Eleven men died and it was said that the survivors had been forced by necessity to consume the flesh and the blood of their dead companions. Five men were eventually rescued by the Naturalist, also out of Calcutta.

Captain Robert Sewell left a widow Anna Maria and two little girls, Esther aged six and Wilhelmina aged two.

By 1871 Commander Henry Sewell was a widower living with his married daughter Mary Anne Bell and her daughter Isabella at Collingwood Villas, Stoke Damerel, Devon.

Commander Henry Frederick Sewell, RN, died aged 86 from bronchitis at 23 Athenaeum Street, Plymouth, Devon, on 29 March 1877. His granddaughter Esther Fanny Bell of 5 Collingwood Villas, Stoke Damerel was present at death.

Acknowledgements:

Ancestry.com and The British Naval Biographical Dictionary (1849)