By Maureen Storey

This article was published in the August 2023 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

One of the more unusual of findmypast’s recent additions to their data collection is Lorenzo Sabine’s Notes on Duels and Duelling, which he published in Boston, MA, USA, in 1855. The book recounts 1855 honour-based challenges most of which took place in England, Ireland, Scotland, USA and France. As usual with such new additions to findmypast, I couldn’t resist a quick search of the index for the Society’s names and was very surprised to find two entries for Americans named Soulé.

The book describes how in 1853 Pierre Soulé, the US Ambassador to the Court of Spain, together with his wife Mary and their son Nelvil (his name erroneously appears as Neville in the book and some other records), attended a ball in Madrid given by the French Ambassador to Spain, the Marquis de Turgot. On overhearing the Duke d’Alba make what he considered to be an insulting comment about his mother, Nelvil immediately challenged the Duke to a duel. The pair named their seconds and swords were the weapons chosen for the combat. The resulting sword fight lasted for about 30 minutes, with neither side gaining victory before it was stopped by the seconds, who declared that honour had been satisfied. The duellists then shook hands and it was thought that the matter was settled.

However, Pierre Soulé still felt aggrieved by the insult to his wife and issued a challenge to the Marquis de Turgot, saying that the Marquis, as host of the ball, did nothing to restrain the Duke d’Alba and therefore was responsible for allowing the insult. (Some reports even state that Soulé accused the Marquis of being the original source of the insult.) Although the Marquis denied being responsible for the offence, he could not ignore the challenge and declared that his weapon of choice was the pistol. Two shots were fired in the ensuing duel, the second of which hit the Marquis in the leg, while Soulé was unscathed.

So who were this hot-tempered father and son?

Pierre Soulé was born in 1801 in the village of Castillon-en-Couserans in the French Pyrenees. He studied at a Jesuit college in Toulouse and then at an academy in Bordeaux and it was while he was at the latter that his anti-Royalist politics and his pro-secularism landed him in trouble and in 1816 he was exiled to Navarre. He was later allowed to go to Paris, where he passed his bar exams and began practising law. However, his interest in civil rights soon got him in trouble again and he was sentenced to three years in prison for opposing the government. Pierre escaped France before he could be incarcerated and headed first to the UK and then briefly to the French colony in Haiti. He went from there to the USA, and in about 1826 he settled in New Orleans, Louisiana, which as a former French colony still had a large ethnically French population and where French was still commonly spoken.

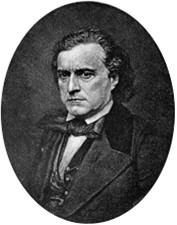

Pierre then set about learning English and passing his US law exams. Once he was established he married Henrietta Armantine Mercier and their son Nelvil Alfred was born in New Orleans in 1831. He became a US citizen and after a failed attempt at starting a bank, in 1839 he returned to practising law, representing mostly cotton planters and brokers. His law career progressed to such an extent that he was associated with most of the celebrated contemporary legal cases, both civil and criminal, in Louisiana. Pierre also began to take an active part in politics. A Democratic party member, he was elected to the Louisiana State Senate in 1846 and served as a US Senator for Louisiana in 1847 and again from 1849-1853. He resigned from the Senate in 1853 to take up the post of US Ambassador to Spain in 1853, a position he held until 1855. His time in Spain was not without controversy, however. Not only were the duels fought by himself and his son considered public scandals by the newspapers, but even worse in 1854 Pierre wrote the Ostend Declaration, which laid out the rationale put forward by some Southern politicians that the USA should annexe Cuba, by force if necessary. As Cuba was at that time owned by Spain, it seems a foolhardy action for the US Ambassador to Spain!

Although Pierre was a vociferous opponent of the secession and predicted that it would end in disaster for the southern states, he nevertheless offered his services to the Confederacy on the outbreak of the US Civil War. However, his service was short-lived as ill-health meant he had to return to New Orleans, where he remained until the city fell to Union forces in 1862. Pierre was captured by Federal troops, charged with plotting treason against the US Government and imprisoned in Fort Warren, Massachusetts. He escaped and went first to Nassau in the Bahamas before returning to Confederate territory. At the end of the war he spent some time in exile in Cuba, but later returned to New Orleans, where he died on 26 Mar 1870.

Like his father, Nelvil Soulé trained as a lawyer and at the time of the duel was working as his father’s private secretary. He returned to the USA with his parents in 1855 and began practising law in New Orleans. On 24 Dec 1856 he married Angele de Marigny Sentmanal, the daughter of a distinguished Mexican revolutionary, whose family had found refuge in New Orleans. The couple had one son and three daughters. At the outbreak of the US Civil War Nelvil volunteered for service with the Confederacy, becoming a captain in D Company of Cazadores Espagnoles in 1861. He was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the same regiment in 1862, before becoming Assistant Adjutant General, Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida under General Beauregard, stationed in Charlston. His duties in Charlston seem to have been largely administrative and included censoring post that passed between families split up by the war and overseeing the conditions of the Union prisoners-of-war held in Charleston’s prison.

After the war Nelvil returned to New Orleans and resumed his legal career. He died on 11 Dec 1878 after a protracted illness. On his death certificate the cause of death was given as ‘softening of the brain,’ a condition that would nowadays almost certainly be called dementia.