By Tony Storey

This article was published in the August 2021 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

Throughout the nineteenth century it was commonplace to see amputees begging in the streets of our towns and cities. Most of these men were ex-servicemen, who had lost their limbs in the many conflicts our army and navy were involved in. No wonder then that army field doctors and ship’s surgeons were often nicknamed ‘sawbones’.

During the American Civil War 1861-1865, most of which was fought on land, 28 per cent of limb amputations resulted in death. It seems entirely possible that similar operations carried out in the heat of naval battles would have an even worse fatality rate. We might wonder why such operations were carried out at all, until we consider that damaged flesh and bone is the perfect breeding ground for bacteria and in the absence of antibiotics, death is the most likely outcome unless the limb is removed.

The presence of surgeons on ships goes back to Roman times, when the Emperor Hadrian decreed that every warship in his navy must carry a trained surgeon, and he would be paid twice the salary of a regular officer. The term ‘sawbones’ seems disrespectful and undervalues the skill and training required to perform necessary surgery in a challenging environment.

The Royal Navy also carried trained medical men aboard its warships. To become a ship’s surgeon a man had to pass an examination at the

Barber-Surgeons’ Company. Once appointed to a ship, he was responsible for the health and well-being of everyone aboard. Surgeons were required to keep two logbooks with details of the treatments and procedures carried out during the voyage and on returning to port one book had to be delivered to the Barber-Surgeons’ Company and one to Greenwich Hospital.

Under the surgeon’s supervision were assistant surgeons and boys. The gruel often served in the sick bay was called loblolly and the boys became known as loblolly boys.

The surgeon’s duties included responsibility for his assistants and boys. Patients were visited at least twice a day, and accurate records were kept of each patient admitted to his care. Every morning the surgeon would take sick call at the mainmast, aided by his assistants, as well as attending injured sailors as required. In addition to caring for the sick and wounded, surgeons were responsible for regulating sanitary conditions on the ship. In order to control the spread of disease, all decks, especially the sick bay, would be fumigated by burning sulphur. Even the ventilating machines, which supplied fresh air to the lower decks, were the surgeon’s responsibility. During sea battles, the surgeon worked in the cockpit, a designated area near a hatchway, enabling wounded men to be brought in for treatment. Sand was put down on floors to prevent the crew from slipping in the blood that was bound to accumulate. A surgeon was very well paid and was a warrant officer of wardroom rank, equal to a commissioned officer.

John Scutt (or Scott) Sole was born in about 1794 in Sheerness, on the Isle of Sheppey, Kent. He was a carpenter and shipwright and in 1817 he married Mary Wycatt in Rochester, Kent. His early career coincided with the building of a new dockyard at Sheerness providing him plenty of opportunities. He was soon to become Inspector of Shipwrights at HM Dockyard, Sheerness.

John and Mary’s first child was born in 1819 and was christened John after his father, as was the family custom. Baby John died in 1821, so when the couple’s second son was born in July 1823 in Sheerness, he too was named John.

The family moved to Chapel Street, Minster-in-Sheppey, and had several more children before Mary’s death in 1834 aged 41.

John Scutt Sole remarried and had a second family. Nevertheless his senior position in the dockyard enabled him to ensure his eldest son received a good education.

By April 1845 John Sole junior was an assistant surgeon attached to the training ship HMS Victory pending his appointment to active service. Between 1846 and 1854 he served his apprenticeship as a surgeon’s assistant on a variety of vessels from sailing brigs to paddle sloops and frigates, including HMS Arab, Dee, Tyne, Centaur and Madagascar. In HMS Centaur, a wooden paddle frigate, he visited the Falkland Islands.

In April 1854 he became surgeon in charge on HMS Sharpshooter, one of the first iron steamers with screw propulsion to be used by the Royal Navy. Britain had a treaty with Portugal, and later Brazil, to suppress the slave trade. Sharpshooter had been deployed off the Brazilian coast and had already captured and destroyed a large number of ships found to be carrying slaves.

Later that year John Sole transferred to HMS Express, where he was appointed Ship’s Surgeon.

HMS Express had been built in 1835 and was a packet brig, a wooden sailing ship designed to convey mail, passengers and freight, often on a scheduled service.

The surgeon’s medical log for the period from 1 July 1855 to 20 September 1856 confirms that Express was employed in the Brazils. It also reveals that John Sole himself was placed on the sick list in June 1856 and sent ashore to be treated in Santa Isabel Hospital, Rio de Janeiro. Some entries from his journal are below.

John Sole joined HMS Retribution as Ship’ Surgeon in March 1857. HMS Retribution was a first class frigate with paddle propulsion and carried 10 guns. Built at Chatham in 1844, she had seen service in the Crimea, but had returned to England by June 1856.

| Extract from John Sole’s Journal from HMS Express, 1855-1856 John Sole, aged 34, Surgeon; debilitas (exhaustio), this was the surgeon own case, was one of utter prostration, consequent on long continued physical exertion and mental anxiety, having been at sea more than 3 weeks without rest night or day; put on sick list 1 June 1856, sent 1 June 1856 to Hospital, returned 1 July 1856. Richard Giles, aged 29, Boatswain’s Mate; contusio, severe injuried (sic) of the foot and great toe, caused by accident when cleaning the ship; put on sick list 5 June 1856, discharged 18 July 1856 to duty. John Marshall, aged 21, Gunner’s Mate; dysenteria; put on sick list 5 September 1856, sent 10 September 1856 to Haslar Hospital. |

The ship was commissioned on the 24th of August, 1856, by Capt. C. Barker, since which time she has sailed and steamed upwards of 70,000 miles, and gone round the world. She commenced her cruise by taking supernumeraries to Malta. She ultimately sailed from Plymouth on the 16th of March, 1857, touching at Rio de Janeiro, and putting into the Falkland Islands to repair the rudder, which had become damaged in a gale of wind after leaving Rio, passing through the Straits of Magellan, and arriving at Valparaiso on the 3rd of July, 1857. During the next nine months she cruised along the coasts of Peru and Chile, protecting British property, and watching the movements of the revolutionary frigate Apurimac. She next received orders to proceed to China. She called at Honolulu, and arrived at Hong Kong on the 12th of June, 1858:

She accompanied Lord Elgin to Jeddo, and transferred the yacht presented by Her Majesty to the Emperor of Japan, calling on the way at Nangasaki and Simeda. The treaty being signed, she returned to Shanghai, and thence proceeded to the Yang-tze-Kiang, having to engage the rebels at Nankin in passing. She conveyed Lord Elgin 450 miles up the river, when, owing to the shallowness of the stream, his Lordship left the Retribution and went on board HMS Furious, which conveyed him about 230 miles further on to Hungchow. She returned to Shanghai from this navigation in unknown waters, the greater part of which was marked by the ship’s keel on the sands and mud of the river, reaching Hong Kong on the 26th of January, 1859, when Capt. Barker was invalided home, and succeeded in the command by Capt. P Cracroft, who was also superseded on the 27th of April following by Commodore H. Edgell C.B., who commanded her for the remainder of the voyage. In July 1859 more than 5,000l was recovered from the wreck of the Ava, near Trincomalee.

Since then Retribution has accompanied the vessels laying down the submarine telegraph cable from Kurrachee to Aden, via Muscat and the Kooria Moorla Islands. She sailed from Aden on the 29th of February, 1860, and arrived at Bombay on the 20th of March, where the ship was placed in dock and underwent very extensive repairs to enable her to reach England. She sailed from Trincomalee for England on the l5th of September, and arrived at Portsmouth on the 9th of December in a terribly disabled state. Fortunately for the safety of all on board, fine weather had been experienced the greater part of the passage. During the whole period of her commission she has lost four officers and 23 men by death, and five officers and 76 men have been invalided.

Sadly John Sole junior died on board Retribution in June 1860 aged only 36. Before joining HMS Arab for his first major voyage in 1848, John made a will. Probate was completed in May 1861, by which all his property was inherited by his sisters, Mary and Caroline, and his youngest brother, Charles.

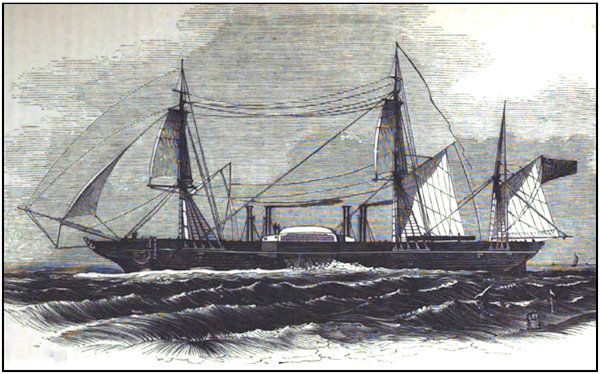

A paddle steamer of the type John Sole served on

The following newspaper account of December 1860 describes John’s final voyage.

HMS Retribution was paid off at Portsmouth in a manner highly creditable both to officers and men. Good conduct medals and gratuities of 15l each were given to three of her crew: James Grant, boatswain’s mate, 24 years’ service; Richard Lee, captain of the forecastle, 24 years’ service; and Robert Gould, quartermaster, of 21 years’ service. The crew was a body of men such as are seldom seen together now in one ship. Many of her A.B.’s left England as “boys.” The appearance of the men at the pay-table sustained the character they had hitherto borne in the ship, for, although an extra degree of liberty has been allowed them during the process of clearing out and returning stores, not a single man appeared to be the worse for liquor; all were clean, smart, and respectable.

John’s father, John Scutt Sole, former Inspector of Shipwrights at HM Dockyard, Sheerness, died in July 1860 on the Isle of Sheppey, just weeks after hearing of his son’s death.

John Scutt Sole’s career in Sheerness began with wooden sailing ships, but he also saw the construction of HMS Salamander in 1832, one of the first paddle steamers in the Royal Navy.

For warships, it was obvious that screw propulsion had some advantages over paddle propulsion. For example, a paddle wheel was an easy target for enemy fire, whereas a propeller and its machinery were below deck. Also, the space taken up by paddle wheels limited the

number of guns a warship could bring to bear. However, the paddle was proven technology, whereas the screw was untested, so the Royal Navy needed proof that the propeller was an effective propulsion system. It was only in 1840, when the world’s first propeller-driven steamship, Archimedes, successfully completed a series of trials against fast paddle-wheelers, that the Navy decided to conduct its own trials.

In 1843 HM Dockyard, Sheerness, was chosen to build HMS Rattler, the first warship to use screw propulsion. Between 1843 and 1845 the Navy pitted Rattler against a number of paddle-wheelers. These trials proved conclusively that the screw propeller was at least as efficient as the paddle wheel. The most famous of these trials took place in March 1845 when Rattler conclusively beat HMS Alecto in a series of races, followed by a tug-of-war contest in which Rattler towed Alecto backwards at a speed of 2 knots. Various types of propellers were also tested on Rattler to find the most effective screw design.

John Sole junior served on a variety of ships as technology improved, but the nature of a ship’s surgeon’s duties changed little during his lifetime. As well as the serious injuries he had to deal with, disease was rife on ships and treatment was fairly primitive. It would be another seven decades before penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming, and not until 1942 that it was first used to treat streptococcal sepsis.

A dockyard at Sheerness had existed since the war with Holland in 1665, but it was closed in 1960 and became a commercial port. Sadly most of the buildings listed as being of special architectural or historical interest have since been destroyed.

The last surviving small ship of Queen Victoria’s Royal Navy and the only survivor of the many vessels built at Sheerness is HMS Gannet, a composite screw sloop built in 1878. She is listed on Britain’s National Register of Historic Vessels and is preserved at The Historic Dockyard, Chatham.

HMS Gannet, the last surviving small ship of Queen Victoria’s Royal Navy. Photo Tony Storey