By Tony Storey

This article was published in the April 2021 edition of Soul Search, the Journal of The Sole Society

William Henry Soule was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1847. He moved to California and found employment as a waiter, but at Sacramento in January 1865 he enlisted in the Union Army as a bugler. He was 18 years old and unmarried. Private Soule was mustered into Company A, 2nd California Cavalry, at Camp Union. He was court martialled in March 1865 and confined without pay until 16 May 1865, he then returned to duty until he was mustered out in April 1866. After the Civil War he remained in California, living in Solano County in 1869 and Kern County in 1875.

In the late 1870s a former United States Army scout, Ed Schieffelin, was prospecting for precious metal in south-east Arizona. Soldiers warned him that he was in Apache territory and if he encountered any braves, he was more likely to find his own tombstone than any gold or silver! He persevered and in 1877 he struck a rich seam of silver ore. Schieffelin filed his claim and named the spot ‘Tombstone’. The settlement grew rapidly into a prosperous mining town.

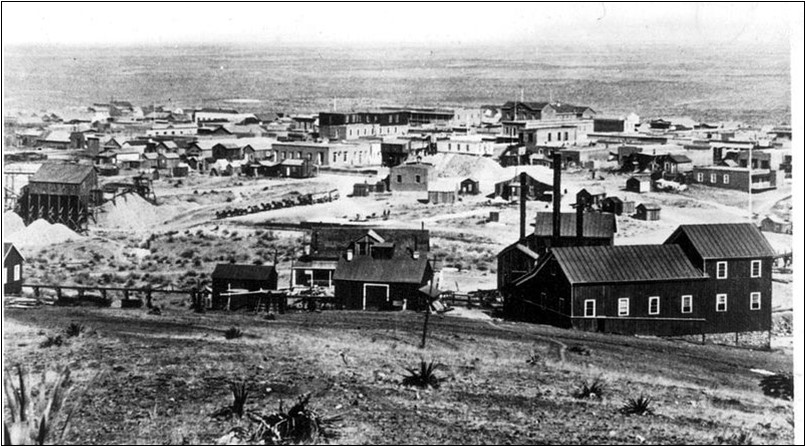

The Town of Tombstone about 1881

By 1880 William Soule had moved to Tombstone and the United States census of 1880 for Allen Street lists family number 169 as William H Soule living alone. Billy, as he was known, was a farmer, aged 33 at the time of the census. His father was born in Maine and his mother in Ireland. As well as working a farm, Billy Soule was a jailer and deputy sheriff of the newly formed Cochise County.

A few doors away in Allen Street, family number 165 is listed as Virgil W Earp and his wife Allie, Wyatt S Earp and his wife Mattie, and James C Earp, his wife Bessie and daughter Hattie. Wyatt Earp had been a police officer in Witchita and Dodge City, Kansas, before arriving in Tombstone in 1879. Virgil Earp had been a

miner and soldier, and became Tombstone’s town marshal in 1880. Morgan Earp, a younger brother, arrived later in 1880, as did as one of Wyatt’s friends from Dodge City, John ‘Doc’ Holliday. Holliday had been a dentist, but had gained a reputation as a gambler and gunfighter.

By 1881 Tombstone had a population of more than 7,000, but as well as being a magnet for those seeking to make their fortune, it had gained a reputation for violence and lawlessness.

The Earps and their friends claimed to represent law and order in Tombstone, but they had other interests and sources of income, such as stakes in mines, saloons and providing private security.

The main opponents to the Earps’ version of law enforcement was a band of cattle ranchers known as the ‘Cowboys’, whose income was largely based on cattle rustling. Tombstone was about thirty miles from the border with Mexico and the Cowboys raided on both sides of the border to provide beef for the new towns that had sprung up around the silver mines. Prominent among the Cowboys were two sets of brothers, Ike and Billy Clanton and Tom and Frank McLaury.

The friction between the two groups was not about any one incident of cattle stealing or heavy-handed policing, it was about which group would control the town and its burgeoning wealth. The intense rivalry boiled over at 3 o’clock on the afternoon of 26 October 1881, when the two factions clashed in a vacant lot behind the Old Kindersley horse corral at the end of Fremont Street, Tombstone’s main thoroughfare. When the sound of gunfire ceased after less than a minute, three men lay dead and three more were wounded. This brief incident became known as the Gunfight at the OK Corral and is one of the enduring legends of the Wild West.

Wyatt Earp was unhurt, but Virgil and Morgan Earp were wounded, as was Doc Holliday. In contrast, three Cowboys, Billy Clanton and the two McLaury brothers, had been killed and Ike Clanton and another Cowboy called Billy Claiborne had fled the scene.

In Tombstone, law officers had the legal right to shoot armed opponents threatening to kill. However, Earp’s group was accused of firing at five unarmed men, leading Sheriff John Behan of Cochise County, Billy Soule’s boss, to arrest the Earp brothers and Holliday on a charge of murder.

Justice Spicer convened a preliminary hearing on 31 October to determine if there was enough evidence to go to trial. The hearing lasted thirty days and testimony was obtained from a great many witnesses, including Billy Soule, who swore that when he took Frank McLaury’s and Billy Clanton’s horses to Dunbar’s livery stables their rifles were in their scabbards.

Another witness claimed that just before the fight he heard Virgil Earp say that rather than arrest the Cowboys, he intended to kill them on sight.

After hearing all the evidence, much of which was contradictory, Justice Spicer ruled on 30 November that it had been proven that two of the cowboys had been armed. Therefore Virgil Earp, as the lawman in charge that day, had acted within his office and that there was not enough evidence to indict the men. Some people in the town disagreed.

The survivors of the gunfight suffered contrasting fates.

One month later, in December 1881, Virgil Earp was ambushed by unknown assailants and shot three times in the back. He survived, but his left arm was smashed and he was left permanently maimed.

In March 1882 an unknown assassin fired a rifle through the rear window of a Tombstone saloon, killing Morgan Earp as he played billiards with his brother Wyatt.

Joseph Isaac ‘Ike’ Clanton remained involved in cattle rustling, but in June 1887 he was shot while attempting to evade arrest and died of gunshot wounds.

The most famous participant at the OK Corral was Wyatt Earp. When his brothers were attacked in the months following the gunfight, there was not enough evidence to convict the obvious suspects. Wyatt Earp was a Deputy U.S. Marshal and he obtained warrants for the arrest of a number of Cowboys. He then deputised eight associates, all known gunmen, to form a federal posse. The stated intention was to bring the suspects to trial, but after a Cowboy named Frank Stilwell was gunned down at Tucson, a warrant was issued for the arrest of Wyatt Earp and his posse on suspicion of extra-judicial murder. By the end of what became known as the Earp Vendetta Ride, four Cowboys had been killed and Earp escaped his warrant by crossing the border into New Mexico Territory.

Wyatt Earp was a professional gambler, lawman, saloon keeper, racehorse owner, gunfighter and boxing referee. Somehow he survived all this to die peacefully at his home in Los Angeles in January 1929 aged 80. It is said that in all his gunfights, Earp never suffered so much as a scratch.

William Henry Soule was not a flamboyant character like Wyatt Earp. After the infamous gunfight and the collapse of the case against the Earps, Billy Soule remained a jailer and deputy sheriff in Tombstone for a couple of years, but indicated that he was ready to adopt a more domestic life. In June 1883 Billy was at least 36 years old when he married Genevieve ‘Jennie’ Belle Goldston in Tombstone. Jennie was only 15 years old and it may have been an arranged marriage with a mail-order bride. Billy may have preferred to leave behind his life in Tombstone, but when he and Jennie moved to Yuma, Arizona, in 1884, the Yuma Sentinel newspaper announced that ‘William Soule, the well-known deputy sheriff of Cochise County, and his family will occupy one of the Modesti Cottages on First Street’.

Billy and Jennie’s daughter, Marie, was born in 1889. In 1891 the Soules were living in Los Angeles, where Billy sold his saloon business for $1500. Their son, William, was born in 1892. The couple had two more daughters, Genevieve ‘Jennie’ Belle born in Sacramento County in 1895, and Mona born in 1898.

By 1902 Billy was again living in Cochise County, at Bisbee, where he was employed at the copper mine. In January 1910 he was admitted to the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers at Sawtelle, California.

At his own request Billy left the Sawtelle soldiers’ home in April 1916 and died aged 69 at his wife’s Los Angeles residence two months later. He was buried in the Los Angeles National Cemetery. Jennie filed for a Civil War widow’s pension in Los Angeles in October 1916 and she died in 1940 aged 72.