EDWARD SOLE

A Much Travelled Colonist

By Linda Butler

This article was originally published in the August 2011 edition of Soul Search, the journal of The Sole Society

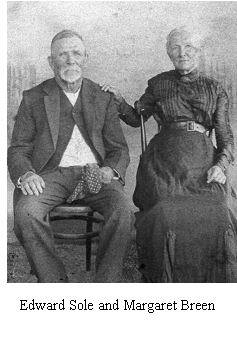

I

knew the basic details about the life of Edward Sole, my great-great

grandfather. I knew he was born in Kelshall, Hertfordshire, and came to

Australia as an 18 year old; that he married Margaret Breen in 1860 (pictured

below) and that he worked as a miner in the goldfields of New South Wales and

Queensland. This information can be gleaned either from basic records, or from

an obituary written about him at the time of his death (it was the basis of an

article by Marge Smith in the April 2003 edition of Soul Search). But there

wasn’t a lot of ‘flesh’ on the ‘bones’ of his story.

I

knew the basic details about the life of Edward Sole, my great-great

grandfather. I knew he was born in Kelshall, Hertfordshire, and came to

Australia as an 18 year old; that he married Margaret Breen in 1860 (pictured

below) and that he worked as a miner in the goldfields of New South Wales and

Queensland. This information can be gleaned either from basic records, or from

an obituary written about him at the time of his death (it was the basis of an

article by Marge Smith in the April 2003 edition of Soul Search). But there

wasn’t a lot of ‘flesh’ on the ‘bones’ of his story.

I unexpectedly came across the obituary again on a recent trip I took with my mother to the Queensland goldfield towns. We were in Eidsvold, where my grandmother Hilda Sole was born. In the small local library, an enthusiastic young librarian unlocked the family history cabinet for us to investigate. In there we found a folder of obituaries, which included the one for Edward Sole that Marge Smith had referred to.

Visiting many of the goldfield towns where the Soles had lived, and reading the obituary again, awakened a desire to find out more about Edward’s life in Australia. I also realised that it might now be possible to flesh out some of that story because late in 2009 the National Library of Australia launched its Trove website(1). Trove is an indexed, full-text database of Australian newspapers, articles, books, photos, diaries and a range of other material. The database currently contains 240 million “works”, of which 129 million are classified as journals, newspaper articles and research. It is an amazing resource, not least because it is free to access, and is a “gold mine” for family historians (pun intended!).

I had already had a bit of a “play” with Trove, and had found several articles on the academic achievements of Edward Sole’s female descendants (that’s a story for another issue of Soul Search). I was therefore aware of some of its quirks. All the newspaper articles on Trove have been converted into text by OCR software, and as anyone who has dabbled in this will know, it’s far from 100% accurate, particularly where the scans are of old newspapers. I found “Sole” indexed on occasions as “Bole” or “Solo”, so I knew it was important to think laterally when searching for relevant information. The problems notwithstanding, it yielded an amazing amount of information on Edward and his brother Daniel, and I was able to put quite a bit of ‘flesh’ onto their stories.

As we know, Edward and Daniel Sole arrived in Australia on board the Lantana in 1856. Within a year they took part in the Araluen gold rush, some 220kms south west of Sydney (“as the Cocky flies”(2)). Edward’s obituary mentions a highly lucrative partnership with William Thorpe, and claims reaping as much as £100 to £180 a week from their mining venture (between £7,000 and £13,000 in today’s money). His financial success is supported by his purchase of the license of a hotel in Araluen, followed by a trip back to England with his family. He had married Margaret Breen in the nearby town of Braidwood in 1860, and his first two sons were born in Araluen – James in 1862 and Edward Goodman in 1865. However, the rewards were not instantaneous, and many hardships had to be overcome, not least the devastating floods of early 1860 (1860) - the Sole brothers and their associates were recipients of £20 from the disaster relief fund (4).

I wanted to find out more about the brothers’ return visit to England. After much searching in Trove, I eventually found a newspaper report of the family’s departure to England on La Hogue, leaving Sydney on 10 January 1867 (5). The newspaper also confirmed Marge’s Smith belief that they were accompanied to England by his brother Daniel and Daniel’s wife Mary Ann. The Sole’s father, Goodman, had died in 1862 but their mother Ann was still alive and no doubt was delighted to her two sons and their families – one suspects that she never expected to see them again after their original departure from England. Indexes to the passenger lists for incoming ships can be readily searched on-line, and I soon found Edward and his family returning to Sydney on the Sobraon on 7 January 1868 (6). Fellow passengers on this voyage included the Earl of Belmore, who was arriving to take up his position as the thirteenth Governor of New South Wales. They were away for just over a year. Daniel and his wife remained in England for longer, not returning to Australia until September 1868, and accompanied by Stephen Sole.

This additional information was interesting, but I really wanted to find out more about Edward’s travels up and down the country between 1870 and 1900 – at a time when most travel would have been on horseback.

On his arrival back in Australia, Edward returned to his agricultural roots and purchased a farm at Foxlow Gap, near Braidwood. While living there he was a witness in the trial of four men accused of the Goulburn Mail robbery in May 1869 (7). His main evidence appears to relate to seeing one of the accused – the son of a neighbour – with a suspicious “small bundle” in front of his saddle early one morning. Then later that day he saw the accused again riding “a bright bay horse”.

Edward’s previous successes soon lured him back to prospecting for gold. It appears there were still significant funds left from earlier finds – some time after the return of Daniel, the brothers purchased the “Iron Duke” ore crushing machine. At the time, the machine cost in the vicinity of £1,200 – the equivalent of at least £100,000 today (8). Their machine, known as an “Iron Duke”, was used to crush ore on the gold fields at Major’s Creek, near Araluen, and would have returned a steady income for the brothers – at round this time charges for the use of the machine ranged from 25s. per ton for small quantities (3 to 10 tons), with rates gradually reducing down to 15s. per ton for large quantities (more than 100 tons) (9). Miners had to pay an additional fee for carting the ore to the crusher. On one occasion, the papers reported that the Soles had 150 tons “to grass” (i.e. ready for crushing), which would have returned the tidy sum of £188, even at the lowest rates (10). It was clearly a lucrative endeavour, though the costs were also high – they employed a large team of men to operate the crusher – so the brothers also worked their own claims. Edward’s third son, William, was born at Major’s Creek in 1869.

In 1871 there were reports of a rich new source of gold at Bredbo, near Cooma, some 68 kms from Major’s Creek. Initial stone raised from these claims was brought to Major’s Creek for crushing by the Sole’s machine. Perhaps in a sign of things to come (Australians love to gamble), newspapers reported several bets on how much gold would be found in these first test extractions (11). The amount extracted was sufficiently promising to prompt the brothers to move their machine to Bredbow, and also become shareholders in a prospecting claim (12). This was no simple undertaking. The Iron Duke had to be dismantled and moved 68 kms by cart. The machine left Major’s Creek on 6 November 1871 and was reassembled in Bredbo on 6 December. Newspapers at the time applauded their enterprise and hoped “the energy of the Messrs Sole in supplying the miners with a crushing machine will be rewarded by a rich and permanent quartz reef” (13). Edward’s first daughter, Amy, made an early appearance in the local papers – as the first child born at the Bredbo diggings. However the newspaper had to publish a correction as they originally reported the arrival of a boy! (14).

Before long rumours began to circulate of poor returns from the Bredbo Reefs (15). There was considerable unease, not least because “the enterprising proprietors of the Iron Duke machine will suffer considerable loss if there is any truth in the rumour” (16). Unfortunately the rumours proved correct and, as Edward’s obituary bluntly states, the Bredbo Reefs turned out to be “duds”. The obituary reported that the loss was in the order of £2,000 to £3,000 (between £190,000 and £290,000 in today’s terms).

Until 1871, Edward

had spent 15 years in the Braidwood area – including Araluen, Major’s Creek and

Foxlow Gap – with a foray out to Bredbo, near Cooma. But now even more extensive

travelling was about to begin – gold prospecting was in his blood, and no doubt

with one success behind him he was always hopeful of striking it rich again.

While he travelled long distances, most times he appears to have taken the whole

family with him – or at least summoned them after his initial survey of the new

fields. However, it is unlikely he took them on his first major journey – a trip

of 1800 kms to Charters Towers in northern Queensland, where gold was discovered

in 1871.

After failing to find gold at Charters Towers, Edward was taken on as manager of

a tin mining company at Stanthorpe, in southern Queensland. No newspaper reports

featuring Edward have come to light from this time, but the birth there in 1874

of his fourth son, Walter, confirms the details in the obituary. By 1877 Edward

had moved the family a short distance back into northern New South Wales, to

Boorook near Tenterfield, where his second daughter, Josephine, was born. He was

still living there in 1879 when he was declared insolvent (17). By 1880 he had

moved again to Vegetable Creek, near Inverell, where his last two children,

Mabel (1880) and Maude (1883), were born. Both Boorook and Vegetable Creek were,

unsurprisingly, mining towns – silver, gold and tin.

The whereabouts of the family over the next 7 or 8 years is unclear. Daniel Sole had settled in Guyra in 1882 and remained there until his death in 1908. Edward and his family appear to have stayed in mining areas of northern New South Wales until 1888 when they joined the gold rush to Eidsvold, 450 kms to the north.

He was always hoping for that elusive second big find. According to the obituary, after having little success at Eidsvold, he tried his luck at McDonald’s Flat, then Gympie for a brief period, before heading north to Mount Usher, then south to Mount Perry, where he lived for seven years. Each of these journeys was in the vicinity of 200 kms. Queensland electoral rolls confirmed that by 1913 he had moved to Gayndah, where he remained until his death in 1923.

I calculated that, “as the cocky flies”, Edward had travelled nearly 6,700 kms up and down eastern Australia. And the actual distance taken to travel the routes is likely to be almost double that. The massive amount of miles he travelled in his lifetime can best be appreciated by plotting them onto a map. He was indeed a “much travelled colonist” – and this must be where my travel bug gene comes from.

Notes:

The database can be found at http://trove.nla.gov.au

In calculating distances, I’ve used Geoscience Australia’s “as the Cocky Flies”

distance calculator at http://www.ga.gov.au/map/names/distance.jsp

Empire, Tuesday 21 February 1860, p3.

Braidwood Observer & Miners Advocate, 16 June 1860.

The Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 23 January 1867, p7

The two relevant indexes searched were: New South Wales Assisted Immigrant

Passenger Lists 1828-1896 and Unassisted Immigrant Passenger Lists 1826-1922

Empire, Monday 7 June 1869, p2

The Queenslander, Saturday 16 April, 1869, p5.

The Brisbane Courier, Saturday 20 September 1879, p6.

The Sydney Morning Herald, Monday 19 September 1870, p2.

The Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 20 April 1871, p6.

The Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday 2 November 1871, p3.

Queanbeyan Age, Thursday 23 November 1871, p2.

Empire, Friday 16 February, 1872

Empire, Friday 19 January 1872, p2.

ibid

The Maitland Mercury