Hearing Voices

By Tony Storey

This article was originally published in the April 2007 edition of Soul Search, the journal of The Sole Society

I have always believed that there is far more to family history than births, deaths and marriages. Frankly, there is nothing more tedious than a family tree consisting only of Paul begat John begat George begat …Ringo. I want to ask questions of my ancestors. Who were these people? Where did they live? What work did they do? What was happening around them? Did they look like me? Were they rich or poor? How did they dress? Could they read and write? What did they believe in? How did they speak?

We can answer many of these questions using documentary sources but we will never hear our ancestors’ voices because there were no sound recordings until the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The story of sound recording began when Thomas Edison patented his phonograph in 1878. That year, Edison published a list of ten possible uses for his invention predicting not only recorded music but also the Dictaphone, the Ansafone, talking books for the blind and the speaking clock.

Edison

believed his machine might also be used to ‘create family records, sayings,

reminiscences of family members in their own voices, even the last words of the

dying’. The last element might seem a little intrusive even today. In any case,

recording the family in sound never became as popular as photography. We may be

lucky enough to have some early photographs, but we will never have the

privilege of hearing our great grandparents speak to us. In contrast, our

descendants will be able to study our lives through the wealth of sources we

leave behind in print, on film or in digital recordings. The daily minutiae of

family life today are being saved for posterity on home recorders and future

generations will watch us and hear us speak to them.

Edison

believed his machine might also be used to ‘create family records, sayings,

reminiscences of family members in their own voices, even the last words of the

dying’. The last element might seem a little intrusive even today. In any case,

recording the family in sound never became as popular as photography. We may be

lucky enough to have some early photographs, but we will never have the

privilege of hearing our great grandparents speak to us. In contrast, our

descendants will be able to study our lives through the wealth of sources we

leave behind in print, on film or in digital recordings. The daily minutiae of

family life today are being saved for posterity on home recorders and future

generations will watch us and hear us speak to them.

Edison also foresaw a need to record language and ‘the exact reproduction of the manner of pronouncing’. English is continually changing and developing, reacting to influences and adapting to our needs like any living language. New words might occasionally appear almost overnight; perhaps to meet an urgent need or describe a new development in technology, but other changes, perhaps in pronunciation, are generally gradual processes.

The BBC’s recent series of Robin Hood proved to be controversial. Viewers expecting a traditional version of the legend objected to the absence of Friar Tuck or took exception to a thoroughly modern Maid Marion wearing heavy makeup. Many more took issue with the dialogue, clearly aimed at today’s youth and peppered with current expressions. Did the critics expect the scriptwriters to represent the language of 1200, perhaps by adding the odd ‘gadzooks’ to the conversation? In fact, the actors would have had to reproduce an early medieval Saxon tongue with some Danish and a smattering of Norman French, no doubt suitably modified by an east midland accent. Nobody really knows how it would have sounded in any case and the BBC would have had to provide viewers with sub-titles.

Two

centuries later and Geoffrey Chaucer, a contemporary of Dick Whittington, is

writing the following lines of Canterbury Tales in his London home.

Two

centuries later and Geoffrey Chaucer, a contemporary of Dick Whittington, is

writing the following lines of Canterbury Tales in his London home.

Upon his heed he wered, of laurer grene,

A gerland, fresh and lusty for to sene.

Upon his hand he bar, for his deduyt,

An egle tame, as any lilye whyt.

Nobody knows for certain how these words would have been said but the verse seems to work if spoken with a Scottish accent! The word ‘deduyt’ means ‘diversion or delight’ and is from Old French, so the Norman influence remains.

If we come forward another two centuries to the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, we can read and understand Shakespeare, although not without the occasional problem. Regarded by many as the greatest of our playwrights and poets, it seems strange that many of his rhyming couplets don’t rhyme. But I believe they did when he wrote them, and from his verse perhaps we can deduce how the words would once have been said. Our language is changing all the time. It is not merely that new words appear and others fall into disuse. How we pronounce the words changes too.

Two hundred years after Shakespeare and Britain is at war with Napoleon. In a decade or two the Victorian age will dawn, bringing technological advances and the British Empire at its zenith. Many of our ancestors were fleeing rural poverty and moving to our towns and cities, seeking the means to support their families. Once again we have to rely on literature to hear our ancestors’ voices. I am fairly certain that if my ancestors were to appear in a Jane Austen novel it would be as a chambermaid, coachman or tradesman. I suspect that their conversation, both vocabulary and pronunciation, would not have been heard in a respectable Regency drawing room. Some writers had an ear for dialect and did their best to represent the speech of the working class in their novels. As a Londoner myself, I tend to look to Charles Dickens for guidance in this matter. Perhaps Sam Weller in Pickwick Papers is as near as I’ll get to hearing the voice of my nineteenth century ancestors. If only the phonograph had been invented earlier.

Edison knew that his invention could record the spoken word but I doubt he anticipated that the recordings themselves would one day influence people’s way of speaking. Young people feel a need to belong to the crowd, to be accepted and regarded as ‘cool’. Listening to youths talking on the bus one morning I was struck by how their pronunciation, intonation and vocabulary owed more to urban American music and Australian soap operas than to their native environment.

The music of the time can tell us something about the lives of our ancestors. It has been said that popular music is the soundtrack to our lives, chronicling historical events and reflecting changes in society and in people’s attitudes. Music has performed this role since the time of wandering minstrels and probably before that. Of course, every generation thinks it invented popular music. ‘Before Elvis, there was nothing’, said John Lennon, although he would have been well aware that his parents’ generation had its own musical heroes.

Songs in the 1970s and 1980s expressed disquiet about Vietnam, support for the civil rights movement in America and protest about apartheid and the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela. Similar songs are written today about different wars and different issues. Elton John sang about the death of Marilyn Monroe but later adapted ‘Candle in the Wind’ as a tribute to Diana, Princess of Wales. ‘Fings Ain’t Wot They Used To Be’, written by Lionel Bart in 1959, complains ‘They turned our local Palais into a bowling alley’. Bart’s words captured a moment of social change as cinemas lost out to television. Ironically, an earlier generation might have bemoaned the fact that the very same building, their local Music Hall built in sumptuous style by the Victorians, had been converted into a cinema when moving pictures became popular.

In the decades before the introduction of recorded music, it was the Music Hall that provided the soundtrack for the life of the ordinary man in the street. Popular songs, as now, reflected the times, but not necessarily the big events. On the bus, in the pub or in the hairdressers, people tend not to talk about the things that our descendants will read about in the history books of the future. In conversation at least, the war in Iraq, the nuclear deterrent and the rate of inflation take second place to the latest fashions, the new James Bond, and what happened in last night’s Big Brother.

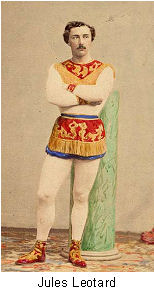

In

the 1860s, a young Frenchman, Jules Leotard, was the sensation of London. As

well as giving his name to an exercise garment, he is celebrated in the song

‘The Daring Young Man On The Flying Trapeze’. Another name well known to the

Victorian public was Charles Wells, a swindler who achieved folk-hero status

when he had a massive win at the casinos. He was later sentenced to eight years

hard labour for fraud but is remembered in the 1891 song ‘The Man Who Broke The

Bank At Monte Carlo’. The 1892 song ‘Daisy Bell’, usually referred to as ‘A

Bicycle Made For Two’, recalls the fascination that cycling held for the

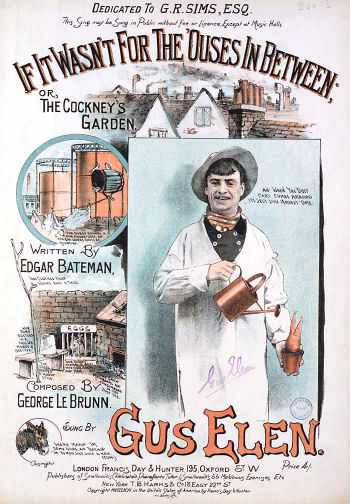

generations that lived in the decades either side of 1900. In 1894 Edgar Bateman

and George Le Brunn noticed how London was expanding into what is now its inner

suburbs, with row upon row of new dwellings springing up to house the increasing

population. They wrote a song called ‘If It Wasn’t For The Houses In Between’.

In

the 1860s, a young Frenchman, Jules Leotard, was the sensation of London. As

well as giving his name to an exercise garment, he is celebrated in the song

‘The Daring Young Man On The Flying Trapeze’. Another name well known to the

Victorian public was Charles Wells, a swindler who achieved folk-hero status

when he had a massive win at the casinos. He was later sentenced to eight years

hard labour for fraud but is remembered in the 1891 song ‘The Man Who Broke The

Bank At Monte Carlo’. The 1892 song ‘Daisy Bell’, usually referred to as ‘A

Bicycle Made For Two’, recalls the fascination that cycling held for the

generations that lived in the decades either side of 1900. In 1894 Edgar Bateman

and George Le Brunn noticed how London was expanding into what is now its inner

suburbs, with row upon row of new dwellings springing up to house the increasing

population. They wrote a song called ‘If It Wasn’t For The Houses In Between’.

My grandmother regarded the Music Hall as not quite respectable. Despite her stated views, she seemed to know all the words and used to sing me the songs that she would have heard as a girl in the 1890s. I have a tape recording of my grandmother speaking in 1963. When I listen to the recording decades later, I am aware of how much her way of speaking reminds me of a different age, not unlike an old newsreel of the Queen Mother. Early recordings from the BBC’s archive demonstrate just how much the language, or at least the style of speech, has changed over the last half-century. Did people really speak like that? Someone recently analysed the Queen’s Christmas broadcasts over the last fifty years and demonstrated conclusively that there have been changes in Her Majesty’s vowel sounds. If the Queen’s English has changed in our lifetime, how can we know how our Victorian ancestors sounded?

One

of the music hall acts of the late Victorian era was the coster comedian. He or

she would assume the identity of a humble street vendor, often singing songs

that reflected the hardship and humour of the workingman’s life. Some of the

earliest street traders in London sold apples, often a variety called costards.

The term ‘costermonger’ eventually came to describe any street trader. Gus Elen

was one such performer, born in Pimlico, London in 1862. He grew up in the city,

learning the songs of the organ grinders and mimicking the patter of the various

tradesmen who walked his local streets. On stage he would appear in a variety of

guises.

One

of the music hall acts of the late Victorian era was the coster comedian. He or

she would assume the identity of a humble street vendor, often singing songs

that reflected the hardship and humour of the workingman’s life. Some of the

earliest street traders in London sold apples, often a variety called costards.

The term ‘costermonger’ eventually came to describe any street trader. Gus Elen

was one such performer, born in Pimlico, London in 1862. He grew up in the city,

learning the songs of the organ grinders and mimicking the patter of the various

tradesmen who walked his local streets. On stage he would appear in a variety of

guises.

Music hall performers were wary of sound recordings, fearing that once the public were able to purchase recordings of their songs, their audiences would dwindle. In any case, by the First World War theatres were closing or converting to cinemas and many artistes had retired, crucially before recordings of any great quality became widely available. However, around 1930, there was a brief revival of interest in the Music Hall and some of the surviving performers were persuaded to make recordings of their most famous songs. Thanks to Edison’s original invention, these recordings have helped to preserve a piece of social history that might otherwise have been lost.

When I listen to the recordings Gus Elen made in 1931, I imagine him dressed as a Covent Garden market porter, imitating the voice of a Londoner who lived in the first half of the nineteenth century. I know it is a romantic notion but I like to believe I am hearing a faint echo of how my ancestors might have spoken nearly two centuries ago.

Oh! It really is a werry pritty gardin

And Chingford to the eastward could be seen

Wiv a ladder an’ some glasses

You could see to ‘Ackney Marshes

If it wasn’t for the ‘ouses in between