The Royal Victoria Hospital

by Tony Storey

This article was originally published in the December 2002 edition of Soul Search, the journal of The Sole Society

From 1854 to 1856 Britain was at war with Russia. Of 54,000 British soldiers sent to the Crimea, 9,000 returned as invalids and a further 18,000 died. Of the dead, only one in ten died of wounds, the remainder and vast majority dying of disease.

Queen Victoria took a personal interest in the welfare of her troops and was moved by the work of Florence Nightingale, who had brought organisation and cleanliness into what had been the filthy, vermin-infested hell of the make-shift hospital at Scutari.

Under

considerable pressure, the British government agreed that a dedicated

purpose-built hospital should be established to care for the sick and wounded

returning from the conflict and land was purchased for the purpose. The hospital

was to be built in Hampshire on a site fronting Southampton Water and the Queen

herself came to Netley to lay the foundation stone in May 1856.

Under

considerable pressure, the British government agreed that a dedicated

purpose-built hospital should be established to care for the sick and wounded

returning from the conflict and land was purchased for the purpose. The hospital

was to be built in Hampshire on a site fronting Southampton Water and the Queen

herself came to Netley to lay the foundation stone in May 1856.

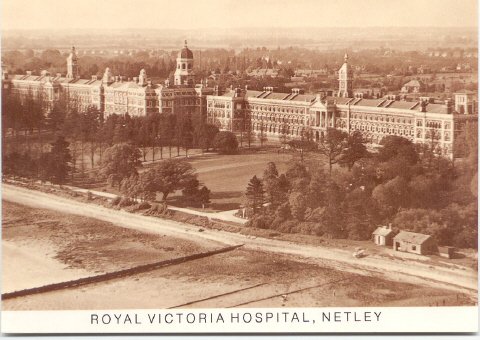

The main building was 468 yards long, one of the longest buildings in the world at the time, and had one thousand beds. A pier was built to receive hospital ships and the hospital’s own ship, the ‘Florence Nightingale’ was able to collect patients from troopships moored off Spithead.

By the time the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley, was completed in 1863, the Crimean war was over but there would be other wars.

*******

Francis Soule was born in the town of Battle, Sussex in 1864, the son of George Soule and Melicent. George was born in Kirk Ella near Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire in 1830 and married Melicent Ansell in Paddington, Middlesex in 1859.

Francis became a grocer’s assistant on leaving school and in the 1881 census was lodging with Mr Allwork, the grocer, and his family at High Street, Battle. However, in May 1883 at the age of nineteen years and one month he enlisted in the Army Hospital Corps. Official records describe him as having a fresh complexion, brown eyes and black hair. He was 5ft 4¾ tall and weighed 121 lbs with a 34 inch chest.

Francis was promoted to sergeant in March 1888. The following month he married Mary Elizabeth Cole at the church of All Saints, Shooters Hill, Kent. In 1891 he was posted to the Straits Settlement, returning to the U.K. in 1895.

By 1899 Britain was at war with the Boers and Francis, now sergeant major, was sent to the conflict in late December that year. Mentioned in despatches, reported in the London Gazette of 10th September 1901, Francis returned in October 1902, having been awarded the Queen’s Medal with clasps for the relief of Kimberley, Paadeberg, Dreifontein and Belfast, and the King’s Medal with clasps for the South African campaign 1901 and 1902.

* * * * *

By the end of the Boer War it had taken 450,000 troops to defeat just 50,000 Boers. As more and more troops had been sent to South Africa, the newly-formed Royal Army Medical Corps was expanded from 3,500 to 8,500 men, yet still proved woefully inadequate for the task.

Although Britain lost only 6,000 men in action, a further 14,000 had died of typhoid. In addition, of the 120,000 Boer civilians imprisoned in concentration camps, 20,000 had died of disease. It was clear from the fatalities that the army had still not learned the value of good hygiene, a lesson preached fifty years earlier by Florence Nightingale and others.

* * * * *

Francis received recognition of his long service and good conduct in 1903 and spent three more years abroad on the island of Mauritius between 1905 and 1907.

On 3 April 1909 Sergeant Major Francis Soule was formally discharged from the Royal Army Medical Corps, No. 5 Company, at Netley, Hampshire and must have thought his military career was over. However, it seems that at the outbreak of war in 1914 experienced men were needed and Francis, though now aged 49, once again answered his country’s call.

* * * * *

Within days of the outbreak of war the British Expeditionary Force of 90,000 men had crossed the channel to France. Known as the ‘Contemptibles’ in defiance of a derisory remark by the Kaiser, 15,000 of them were soon to be casualties and many of the more seriously wounded would be sent to the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley. A further one thousand beds were made available by building the Welsh and Red Cross hutted hospitals behind the main building.

The hospital had its own railway station, constructed in 1900, on a spur off the main line and trains consisting of special ambulance coaches brought casualties landed at the port of Southampton. Empire troops from the fighting in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia were amongst the arrivals in 1915, as were the first victims of gas attacks. In 1916 the bloodbath intensified with the Battle of the Somme. The first day of the battle left 21,000 dead and wounded and by the fourth day there were 33,000 casualties waiting at French ports for evacuation to British hospitals.

* * * * *

Francis’ death in 1919 at the age of 54 is registered in South Stoneham, and an entry in the Principal Probate Registry Index reads as follows:

Francis Soule late of Kelvedon, Hound Road, Netley Abbey, Hampshire (Retd. Ty. Lt. QM R.A.M.C.) died 23 November 1919 at the Welsh Hospital, Netley. Administration (with Will) at Winchester to Mary Elizabeth Soule, widow, 13 November 1920.

* * * * *

During the 1914-18 war the site at Netley comprising the main building and the hutted Welsh and Red Cross hospitals treated approximately 50,000 patients. The fatality rate was about one in eighteen and although most of the dead were claimed by their loved ones for private burial, the cemetery at Netley hospital contains just over seven hundred graves from this period.

One of

the gravestones is inscribed:

One of

the gravestones is inscribed:

G/25201 Private William Ernest Solly,

E Kent Regiment “The Buffs” died 12 October 1918

It is possible that Private Solly had no surviving family to arrange his funeral. We know very little about him although it is believed he is the Willie Ernest Solly born October 1884 at 17 Charlotte Place, Margate, Kent to William John Solly, bricklayer, and Phillis Solly, née Brame. In the 1901 census, William is aged 16, a bookseller’s porter living with his widowed mother at 16 Cowper Road, Margate. On his death certificate he is said to be aged 34, of 4 Manor Place, Ospringe Street, Faversham, Kent. The cause of death was ‘gunshot wound of spine (active service) and septicaemia’.

* * * * *

In World War II the hospital became busy again following Dunkirk and the fall of France in June 1940. The Americans took over the buildings in January 1944, in good time for the D-Day landing, and during the next eighteen months treated 68,000 casualties, including 10,000 Germans! After the Second World War the Victorian building was allowed to deteriorate and although used briefly by the Red Cross in 1956 to house Hungarian refugees, it was finally demolished in 1966, although the Royal Chapel at its heart was preserved.

In 1980 Hampshire County Council acquired the entire site, which is now a country park for the public to explore and enjoy. The Royal Chapel is the focal point and houses a heritage centre with exhibits and a film show to illustrate the history of the military hospital at Netley.

The hospital’s own cemetery is a beautiful and peaceful place, deliberately set apart from the busy hospital complex. Nowadays, a nature trail takes visitors along a raised causeway through dense woodland to the cemetery. It is sad to reflect that during three major conflicts, funeral processions would have walked the same path almost on a daily basis.