The Mysterious Lives of Arthur Saul

by Tony Storey

This article was originally published in the August 2006 edition of Soul Search, the journal of The Sole Society

In 2001, the Beinecke Library acquired for Yale University a

rare 1652 edition of The Famous Game of Chesse-Play by Arthur Saul, the first

chess manual to be written by an Englishman. Who was Arthur Saul and could we

place him on one of our family charts?

The book was first published in 1614 so our search for Arthur Saul, chess

master, would have to start in the previous century. As a background to our

quest, we should keep in mind that our man lived during a very turbulent period

in English history.

England began the sixteenth century as a Catholic country and in the early years

of the reign of Henry VIII, Protestants seeking to undermine the power of the

clergy were persecuted by the likes of Thomas More. Like most Englishmen of the

time, the king was a devout Catholic but was concerned to produce a male heir to

the throne. When the Pope refused permission for Henry to divorce his first wife

and marry Anne Boleyn, the king, aided by his minister Thomas Cromwell, passed

the Act of Supremacy of 1534, which removed the English church from the

authority of Rome. Thomas More was executed in 1535 for refusing to recognise

the King’s authority over the church.

Thomas Cranmer was now Archbishop of Canterbury, a position he held even after

Henry’s death through the short reign of the boy king, Edward VI. During this

time it was the Catholics who were persecuted. In 1553 Edward died of

tuberculosis. After a failed attempt to make Lady Jane Grey queen, Mary, the

Catholic daughter of Henry’s first wife, Catherine of Aragon, took the throne.

During her six-year reign, nearly 300 Protestants were burnt at the stake for

heresy or treason, including Thomas Cranmer.

After the death of Bloody Mary the second Act of Supremacy of 1559

re-established the Church of England under Elizabeth I. However, for both

religious and political motives, there continued to be numerous plots to

overthrow the monarch and restore the Church of Rome,

At first the search for Arthur Saul seemed all too easy. A number of sources

name Arthur Saul as a Gloucestershire-born Protestant clergyman, by 1546 a

fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford, who was exiled abroad during the reign of

the Catholic queen, Mary. Known to have had an altercation with an English

government agent during his exile in Heidelberg, he was able to return to

England after Mary died. Under the Protestant queen, Elizabeth, he rose to

prominence in the Church of England, holding senior posts in Salisbury, Bristol

and Gloucester. Unfortunately, he could not be the author of the chess manual

because he died in 1586. In the terms of his will of 1580, which survives at the

National Archives in Kew, he left property to his five children, including his

sons Arnold and William, who were minors at the time of his death. There is no

mention of a son called Arthur, yet intriguingly, the records of Magdalen,

Oxford, the clergyman’s old college, do include mention of an ‘Arthur Sale’

graduating in 1572.

By 1573 Queen Elizabeth had reigned for fifteen years but the number of

conspiracies had not diminished. Sir Francis Walsingham was then appointed

Secretary of State and is credited with organizing the intelligence service, a

network of spies to counter the threat from foreign powers and also from those

forces within that sought to overthrow Elizabeth and the Church of England. In

1584 it became law that any native-born subject who had become a Catholic priest

at any time since Elizabeth’s succession to the throne in 1558 was guilty of

treason punishable by death.

Mary Queen of Scots had been the focus of several intrigues against the English

government and Walsingham kept her under close surveillance. Eventually, by

intercepting her letters he was able to implicate her in the Babington Plot of

1586 and secure Elizabeth’s signature on her death warrant. Mary was executed at

Fotheringhay in 1587. By this time the population had been conditioned to fear

and distrust all foreigners, particularly Catholics.

At the end of the century we find another Arthur Saul, who was married and

settled in London although he did not spend all his time there. The papers of

the Star Chamber record a complaint by Arthur Saull, a gentleman of London, that

he was staying with his wife at the house of a friend in Gloucestershire in

August 1600 when the house was attacked by sixty armed men claiming to be acting

in the queen’s name and threatening to burn the house and strip his wife of all

her clothes. The link with Gloucestershire could suggest the London gentleman

was in some way related to the clergyman.

Might

it be the same Arthur Saul who, in 1600, reported to Sir Robert Cecil,

the queen’s principle secretary, regarding the unsuccessful surveillance and

pursuit of an unnamed man in the Ludgate and St Paul’s area of London? The man

under surveillance was also sought at Court so we can assume it was someone of

substance that the security service had concerns about.

Might

it be the same Arthur Saul who, in 1600, reported to Sir Robert Cecil,

the queen’s principle secretary, regarding the unsuccessful surveillance and

pursuit of an unnamed man in the Ludgate and St Paul’s area of London? The man

under surveillance was also sought at Court so we can assume it was someone of

substance that the security service had concerns about.

In

February 1601, Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex, stepson of Robert

Dudley, Earl of Leicester and once a favourite of the queen, was arrested for

treason and subsequently executed along with a number of other rebellious young

malcontents. Sir Robert Cecil had also distrusted Sir Walter Ralegh for some

time but was unable to take action while the queen was alive. When Elizabeth

died in 1603 Ralegh was arrested for treason and confined in the Tower of

London. In 1605 the most famous conspiracy of all, the Gunpowder Plot to blow up

Parliament and the King, was thwarted in the nick of time by the security

service. Several Catholics, including Guy Fawkes, were tortured and executed.

In

February 1601, Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex, stepson of Robert

Dudley, Earl of Leicester and once a favourite of the queen, was arrested for

treason and subsequently executed along with a number of other rebellious young

malcontents. Sir Robert Cecil had also distrusted Sir Walter Ralegh for some

time but was unable to take action while the queen was alive. When Elizabeth

died in 1603 Ralegh was arrested for treason and confined in the Tower of

London. In 1605 the most famous conspiracy of all, the Gunpowder Plot to blow up

Parliament and the King, was thwarted in the nick of time by the security

service. Several Catholics, including Guy Fawkes, were tortured and executed.

The authorities remained paranoid and government spies continued to uncover

conspiracies both real and imagined, but there was no further news of Arthur

Saul and we might reasonably have assumed he had died or at least retired from

the fray. In fact, nothing had been heard of him for more than a decade when in

1614 a book was published setting out the rules of chess. Could the author of

The Famous Game of Chesse-Play possibly be the same man who had spied for Sir

Robert Cecil all those years before?

Was it the same Arthur Saul who was sent to the continent in September 1615 by

the Secretary of State, Sir Ralph Winwood, in order to spy on English Catholics?

He is known to have ‘tailed’ priests returning to England and attended a mass,

presumably working undercover, at a house in Petticoat Lane, London, near to the

home of the Spanish ambassador.

The search for Arthur Saul then takes a dramatic turn. On 19 February 1617, an

Arthur Saul is arrested and charged with the rape of Hester Hopkins in the porch

of St Mary Abchurch in the City of London.

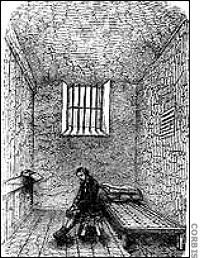

He

finds himself imprisoned in Newgate, where coincidentally a number of

Catholic priests are being held. If this is our man, the situation looks grim

indeed, but there is a further twist in the tale. On 5 April he gives a

statement to the authorities. He tells them he is working for the state secret

service and is able to supply valuable information he has gathered whilst in

gaol concerning the recent escape of two women recusants and two priests.

He

finds himself imprisoned in Newgate, where coincidentally a number of

Catholic priests are being held. If this is our man, the situation looks grim

indeed, but there is a further twist in the tale. On 5 April he gives a

statement to the authorities. He tells them he is working for the state secret

service and is able to supply valuable information he has gathered whilst in

gaol concerning the recent escape of two women recusants and two priests.

Could it be that his arrest had been merely a cover, a device to enable him to

gain the trust of fellow prisoners and gather information? Unfortunately it is

unlikely we will ever know. Prisons at this time, not least Newgate, were foul,

unsanitary places. Arthur Saul became very ill, probably with gaol fever, a

virulent form of typhoid. He died in the prison on 29 April 1617.

So just how many men called Arthur Saul have we discovered?

There was the eminent churchman who died in 1586 who, as far as we know, neither

worked for the intelligence service nor wrote a book about chess.

There were two secret service agents with different signatures – the signature

in Newgate did not match that on the report to Sir Robert Cecil in 1600.

Nevertheless they may have been one and the same man.

Finally there was the author of a world-renowned work on the game of chess who

might have been one, or indeed both, of the secret agents.

Although not conclusive by any means, the final piece of evidence is this. In

1618, a year after the death in Newgate prison, a revised edition of The Famous

Game of Chesse-Play is published. A footnote tells us that its author, Arthur

Saul, is now dead.

Acknowledgement: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography