Lost Souls

The tragic story of five brothers who all lost their lives in the carnage of the First World War

By Michael Walsh

This article was published in the April 2002 edition of Soul Search, the journal of The Sole Society.

This article was originally published in the November 2001 edition of Saga and is reprinted with their permission

It is a picture-postcard village with a proud and tragic secret. A newspaper cutting hanging in the bar of the only pub is one of the few clues, but most visitors cannot see beyond the menu board. Stroll out of the Lamb Inn, past the neat village green and the school is across the road. Annie Souls’s sons would have been pupils there – when they weren’t bunking off to bring in the hay or catch rabbits.

The

Souls family – Annie, William, their six sons and three daughters – lived nearby

in a four-roomed farm-labourer’s cottage long since converted into a desirable

Cotswolds property. At the bottom of the lane is the imposing manor house where

the Souls boys worked as farm hands and next door is the church of St John the

Baptist, with its squat tower and ivy-covered gravestones.

The

Souls family – Annie, William, their six sons and three daughters – lived nearby

in a four-roomed farm-labourer’s cottage long since converted into a desirable

Cotswolds property. At the bottom of the lane is the imposing manor house where

the Souls boys worked as farm hands and next door is the church of St John the

Baptist, with its squat tower and ivy-covered gravestones.

This corner of Gloucestershire is away from the well-trampled tourist paths. That could be why Great Rissington’s secret has stayed so well hidden for more than 80 years. Or perhaps it just doesn’t want to risk a Hollywood invasion. Inside the church is a memorial to the local sons and fathers who went off to war and never returned. It is unusual, because as well as inscriptions there are photographs of the dead men, fading now, but all proud and scrubbed in their uniforms.

On Remembrance Sunday, the congregation stands, heads bowed, while the names are read out. Look at those names and the pictures of these long-dead soldiers and the poignant secret will slowly be revealed – you might just wonder about the fuss over saving Private Ryan: five brave brothers, Albert, Frederick, Walter, Alfred and Arthur, wiped out in the First World War and all but forgotten by the country for which they died. A sixth brother, Percy, stayed at home because he was too young to fight, only to be struck down by meningitis. The Imperial War Museum and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission know of no greater sacrifice by a British family.

Alf and Arthur

were identical twins. Born an hour apart, they died five days apart. Walter

wrote a cheery postcard home from hospital and was dead from a blood clot by the

time it was delivered. Albert, the youngest and, with Walter, the first to

enlist, was the first to be killed. Fred’s body was never found but his mother

kept a candle burning in the window of the house in the hope that he would

return.

Alf and Arthur

were identical twins. Born an hour apart, they died five days apart. Walter

wrote a cheery postcard home from hospital and was dead from a blood clot by the

time it was delivered. Albert, the youngest and, with Walter, the first to

enlist, was the first to be killed. Fred’s body was never found but his mother

kept a candle burning in the window of the house in the hope that he would

return.

Annie Souls received a shilling for each dead son and a letter from the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, in 1916 conveying the “sympathy of the King and Queen for Mrs Souls in her great sorrow” after three of the boys had been killed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Albert Souls aged 20, killed in action, France, 1916 |

Frederick Souls aged 30, missing in action, France, 1916 |

Walter Souls aged 24, died of wounds, France, 1916 |

Alfred Souls twin aged 30, killed in action Flanders, 1918 |

Arthur Souls twin aged 30, killed in action, France, 1918 |

This is one of the scraps discovered from newspapers of the time. I have tracked down surviving family and traced former Rissington residents now as far flung as New South Wales, including Maud Pill, 99, just back from a Caribbean cruise. I have scoured public records, but the search for the brothers has brought mostly disappointment and frustration.

The Fighting Sullivans – five brothers from Iowa who died when the USS Juneau was torpedoed at the battle of Guadalcanal in 1942 – inspired a Hollywood film and had a US Navy destroyer, a park and a convention centre named after them. Each of the boys was awarded the Purple Heart for gallantry and their parents were fêted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House. The tragedy also prompted Roosevelt to swear that no family should lose more than two sons in war.

The first test of this edict occurred with the Nilands. Two of their sons were killed in battle and a third missing in action when the President ordered a remarkable rescue mission to pluck their youngest boy from the war and bring him safely home. It was this extraordinary story which inspired the Oscar-winning film Saving Private Ryan. But the humble Souls brothers are barely remembered even in their home village, except when their names are read out at Remembrance Day services.

The family papers burned for two days

Arthur won the Military Medal for the action in which he was killed but the citation detailing the courage that cost him his life was probably thrown on to a bonfire of family papers that is said to have burned for two days.

The memories of relatives provide only tantalising glimpses of tragedy. The soldiers’ niece, Katherine Hall, 87, of Great Barrington, Oxfordshire, has a flickering childhood recollection of being wheeled around in a pram by a figure in khaki. Katherine, daughter of the brothers’ sister Kate, was brought up by her grandmother and remembers cruel village gossip about how well off Annie Souls must have been with the pensions for five dead sons. “It upset her greatly,” Katherine recalls. “She wouldn’t stand for God Save the King because she blamed him for the war. She stood just once, at my school, so as not to embarrass me but it was painful for her.”

Maud Pill, now living in Newbury, Berkshire, remembers them coming to village dances in uniform. “They were all nice looking, though not very tall – I don’t know why they weren’t married, although Arthur did have a girlfriend who lived with them all in that little cottage,” she said. Bringing in the hay came before education and the boys would have followed their father into agricultural labour by the age of 12 or 13. They could write their names, which are carved into the beams of a village barn. When war broke out in 1914, Albert and Walter quickly joined 2nd Battalion the Worcestershire Regiment. The older boys – Fred, Alf and Arthur – enlisted originally in the 16th Cheshires, a “Bantam” battalion raised to take big-hearted recruits too short for the Army.

From battalion records and through the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, it is possible to pinpoint where they fought and died. After crushing setbacks over destroyed family papers, vanished school archives and faded memories, I was depending on their war records to discover if Walter, Fred, young Albert or the twins had rotten teeth, flat feet or what keepsakes they were carrying when they fell on the battlefield.

Two-thirds of these files on soldiers killed in the First World War were destroyed in the Blitz but the charred and water-damaged remnants are being pieced together and made available on microfilm. My heart was pounding like a Tommy waiting to go over the top as I took the binder for record WO363 – known as the “Burnt Documents” – from a shelf at Kew Public Record Office (PRO) and skimmed through till I came to “S”. I scanned the names and stopped at Soul, Herbert to Soulsby, Robert. I was directed to box number 1936 in one of the rows of cabinets that flank a room whirring with dozens of microfilm and microfiche machines.

I switched on one of the electronic readers and joined the great whirr. Herbert Soul of the Cheshire Regiment came to life in the tattered remains of his service records – first his enlistment papers, detailing his age, weight, height, chest expansion, where he joined up, his next of kin. A barely legible scrawl listed him as one of the first to go to France in August 1914. By August 24, he was posted as missing but the following March he was back from the dead, a PoW in Germany, and was repatriated in 1918. The only crime on his conduct sheet was taking a pear from an orchard in France, for which he was confined to barracks for four days in August 1914.

I checked to see if I had been mistaken

Next came Kenneth McNab Soul. I impatiently pressed the fast-forward... Soulby, Soule, Soulie, Souls. Clarence Herbert Ennis Bowls Souls, from Cardiff. Not one Souls brother. I wound the film on. Still no Souls. I checked the binder to see if I had been mistaken about the film number, but there was no mistake. I frantically tried variations on the name – Soles, Sole – in case a semi-literate Army recruiting officer had made a mistake, just as a registrar had in writing “Soul” instead of “Souls” on Albert’s birth certificate. Still nothing. Except fragments from other lost lives: Will Sole, a blacksmith from Faversham in Kent, whose records include the words “teeth – BAD”; the pitiful list of personal effects of another William Sole of the Royal Scots, killed in action on August 1, 1918, comprising religious book, wallet, photo, letter and postcard.

I grabbed a PRO staff member and asked desperately if the Souls records could still be in the system somewhere. No chance – “It’s just really rotten luck,” he said. That leaves just battalion diaries, often scribbled in the heat of combat, musty smelling and matter of fact, which reveal where the Souls boys were when they died, but which usually mention only officers by name. Albert and Walter sailed to France with the 2nd Worcesters in June 1915 and were soon surrounded by death and knee-deep in mud. In September they were flung into the Battle of Loos, where the British suffered 50,000 casualties. The diary paints a chaotic picture of trenches jammed with dead and wounded in which men risked being gassed by their own side before going over the top into a firestorm of machine-gun fire.

The brothers survived and the Worcesters were singled out for special praise for their gallantry. A month later they were paraded before King George V on a foggy morning. The diary reports that the King’s horse reared and threw him off as he left the parade ground. Inseparable, the Souls lads transferred to the Machine Gun Corps in January 1916 and spent weeks training amid the slag heaps of the bleak, flat mining area around Bethune in Northern France. On March 14, the 5th Brigade Machine Gun Corps war diary reports one casualty. It might have been all quiet on the Western Front but it was the day Annie Souls lost her first son to the war.

Walter was wounded and shipped out

Walter’s unit was hurled into the Battle of the Somme on July 20 – he probably wouldn’t have known that just a day earlier, barely a grenade’s throw away, his brother Fred had gone over the top with the 16th Cheshires, never to be seen again. Walter was wounded and was shipped out to a hospital at Rouen, from where his mother received this letter:

“Dear Mrs Souls, I much regret to have to tell you that your son died very suddenly about nine o’clock yesterday evening. He came to us with a wound in his left leg, and on Tuesday he had to undergo an operation, but he rallied and seemed to be better. He was quite cheery, and then the next evening he suddenly collapsed and died instantly from an embolism (or clot of blood) in the heart. I am enclosing a postcard which he wrote on the day he died. He will be buried in the little British cemetery just outside Rouen where lie other brave lads who have fallen in this dreadful war. This will be a dreadful blow to you and you have our deepest sympathy in your great loss – M. Phillips, Matron, 25 Stationary Hospital, BEF, Rouen.”

The hospital chaplain wrote: “You have both made a great sacrifice – you have given your son, he his life. He seemed quite happy and little did I think that he was so near the end.”

Alf went from the 16th to the 11th Cheshires who were badly mauled at the Somme and reduced to just 100 men – a 10th of normal numbers. “Tired and weary, the men never failed to respond to any exertion demanded of them,” reports the battalion diary. They suffered appalling casualties again at Messines Ridge and Ypres in 1917 and were in the desperate rearguard action at Ploegsteert Wood in Flanders in the German spring offensive of 1918, when Alfred Souls died. The 11th Cheshires fell back 38 miles over one 48-hour period, stopping six times to dig in and being reduced once more to just a handful of officers and a bunch of exhausted survivors.

Alf was not one of the lucky ones – he was killed, aged 30, on April 20, 1918, and is buried in leafy Strand Military Cemetery. Family legend says that Arthur, by then a lance corporal attached to the 7th Royal West Kents, lost all will to live when he heard of his twin Alfred’s death. The West Kents’ diary for April 1918 records orders to hold the Villers-Bretonneux plateau “at all costs”, lists six officers and 228 other ranks killed, wounded and missing and gives a roll of honour, including “Military Medal for 21683 L/c Arthur William Souls (since a casualty).”

He is among

550 soldiers, half of them unidentified, buried in Hangard Communal Cemetery

extension, a place of terrible beauty sloping down towards the winding Luce

River – once running with blood but now as peaceful as the River Windrush near

Great Rissington. Albert is buried at Bully-Grenay in a grim part of Northern

France where the slag heaps remain. Walter is at St Sever Cemetery, Rouen. All

that’s left is the newspaper cutting from after the war in the pub and those

pictures in the church.

He is among

550 soldiers, half of them unidentified, buried in Hangard Communal Cemetery

extension, a place of terrible beauty sloping down towards the winding Luce

River – once running with blood but now as peaceful as the River Windrush near

Great Rissington. Albert is buried at Bully-Grenay in a grim part of Northern

France where the slag heaps remain. Walter is at St Sever Cemetery, Rouen. All

that’s left is the newspaper cutting from after the war in the pub and those

pictures in the church.

The rector, the Rev Sue Moth, says locals know little about the brothers. “Visitors are always very moved by the pictures and are quite astonished to learn that these five brothers who went to war were all killed,” she says. “We hold them very dear because I doubt if there can have been a greater sacrifice.”

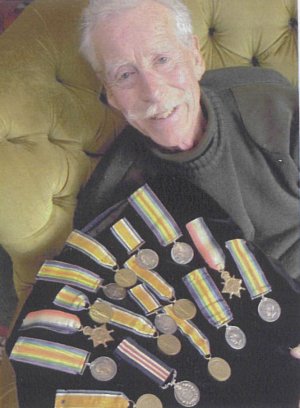

Victor Walkley, 78, is the son of Iris, one of the Souls’ boys three sisters. Born five years after the last of his uncles died, he cherishes their war medals at his home in Holmfirth, West Yorkshire. “I have told my son to hand them over to the Cheshire Regiment Museum in Chester when I am gone,” he says. “In the absence of official recognition, at least they will remind people how much one family suffered.”