by Maureen Storey

This article was originally published in the August 2009 edition of Soul Search, the journal of The Sole Society

On 29 September 1829 passers-by saw for the first time a line of men in tall hats and long blue coats marching down Whitehall and on into the surrounding streets. These were the men of the Metropolitan Police, which was founded by Sir Robert Peel in order to restore order to the increasingly lawless streets of London.

Before this the policing in England was still based on the old 'Watch and Ward' system which was set up in the thirteenth century. Each parish was policed by its parish constables (the number of which depended on the size of the parish, with a minimum of 2), who were appointed by the parish vestry committee. The role of parish constable was extremely unpopular, since it was unpaid, so incumbents had to fit its time consuming tasks around their usual work the more affluent members of the parish usually managed to buy their way out of serving as a constable. In addition. each town was patrolled at night by watchmen, who carried a cutlass and lantern. Anyone apprehended by the night watchmen was handed over to the parish constables who placed him in a lock-up until he could be brought before a Justice of the Peace.

By the 1750s the overall organization of policing in England was in a terrible state: the watchmen were often old and ineffective, parish constables were finding it increasingly difficult to maintain law and order in the towns and cities and the roads were infested with highway robbers.

The first step toward reform came with the introduction of the Bow Street Runners by Henry Fielding in 1753. This was initially a force of just six men who worked from Bow Street Magistrates Court in London. These six proved to be so successful in apprehending criminals that similar forces were soon established at other magistrates courts.

The introduction of the Bow Street Runners brought great improvement but they functioned essentially only as detectives, which is only one facet of policing. What was also needed was a body of men who were able to restore order and keep the peace. Before 1829 any public disorder was quelled by the use of troops and since these were fully armed this often resulted in fatalities: the pacification of the largely unarmed crowd during the Gordon Riots in 1780 resulted in over 200 deaths, and hundreds of injuries, while in the Peterloo massacre of 1819 the use of mounted troops resulted in 11 dead and several hundred casualties.

This

was the situation faced by Sir Robert Peel when he became Home Secretary in

1822. He knew that reform was urgently needed and in the first instance he

decided to reform the policing in London by introducing a single body that

covered the whole of the metropolitan area. His Metropolitan Police Improvement

Bill of 1829 heralded the start of the Metropolitan Police.

This

was the situation faced by Sir Robert Peel when he became Home Secretary in

1822. He knew that reform was urgently needed and in the first instance he

decided to reform the policing in London by introducing a single body that

covered the whole of the metropolitan area. His Metropolitan Police Improvement

Bill of 1829 heralded the start of the Metropolitan Police.

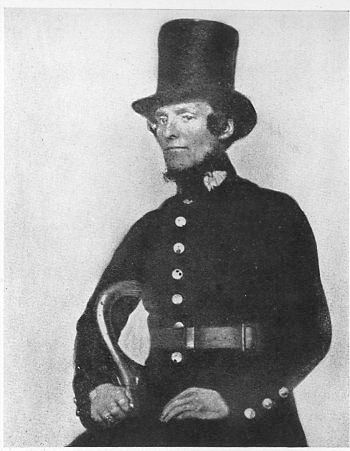

In the beginning the force consisted of just over a thousand men: 8 superintendents, 20 inspectors, 88 sergeants and 895 constables who were distributed between the various divisions, sections and beats into which London was divided. All the sergeants and constables were issued with a blue uniform that they were expected to wear everyday even when off duty! The only difference between their on-duty and off-duty attire was that while on duty they wore an armband. The superintendents and inspectors had to buy their own uniforms. Sergeants and constables wore tailed blue coats with metal buttons, a 4 inch wide leather belt, a 4 inch leather stock (designed to prevent the officer being garrotted), a heavy top hat and boots. In winter they wore heavy blue trousers but in summer they could wear light-weight grey ones (which they had to buy themselves). In addition they were supplied with a great coat and a cape for inclement weather. They were also issued with a baton, a rattle (carried in the breast pocket to protect against knife attacks), a lantern and handcuffs.

This then was the uniform donned by George Sole when he joined the Metropolitan Police on 20 June 1834. George was baptised at St John-at-Hackney on Christmas Eve 1815 and was the youngest child of William Sole and Dinah Woodland. We can only guess why he wanted to be a policeman. Many of his fellow constables were ex-servicemen, but as he was only about 20 when he enlisted that seems unlikely to be the case with George. It is possible that he was influenced by the murder of his sister Ann in 1819 (see Soul Search Vol. 3 No 10, pp. 5052) but it is most likely that he joined simply because the alternative was unemployment. Recruits had to meet strict criteria so the very fact that he was taken on tells us a little about George: he was literate, physically fit, more than 5 feet 7 inches tall, sober and known to be of good character. But what sort of life did he have?

Life for a constable in the 1830s was hard. In the first years of the service, half of the force was on duty between 9 pm and 6 am and the other half took over during the day, though later the proportion of men working at night was reduced to a third. A constable was expected to patrol his beat for his entire time on duty at a steady 2.5 miles per hour, which meant that when on night duty he walked about 20 miles per night, 7 days a week and in all weathers. He was allowed no meal or refreshment breaks during his shift and was forbidden to sit or lean on anything while on duty. The work was physically very demanding and since London, with its smogs and open sewers, was an unhealthy place to work, many policemen had to leave the force due to ill-health: more policemen died of tuberculosis than from attacks by criminals.

In the early days discipline within the force was extremely strict and policemen were dismissed for very minor infractions of the rules such as being late on duty or being improperly dressed. Indeed, just being the subject of a complaint by a member of the public was grounds for dismissal whether the complaint was justified or not. However, the most common reason given for dismissal was drunkenness.

In 1830 in return for all his hard work, a police constable received 1 guinea a week, which was often reduced to as little as 17s 6d after stoppages for his pension and rent (unmarried policemen were expected to live in police accommodation). This was roughly equivalent to the pay of for example a sailor or a quarryman, and was more than that of a labourer, but less than that of a postman or miner. After 20 years (reduced to 15 years in 1862) a policeman was eligible for a pension, but this pension could be, and often was, refused if there was even a minor misdemeanour on the constable's record.

In addition, it took several years for the general public to acknowledge the service's worth. Initially it was regarded as an unnecessary expense and was greeted with open hostility there was even one occasion when the jurors in the trial of a man accused of murdering a policeman returned a verdict of 'justifiable homicide'. Eventually, however the public became used to the police and accepted them as upholders of the law.

The strict discipline, unhealthy working conditions, comparatively poor pay and initial public hostility lead to a high turnover of personnel. Of the 3000 men who joined the force between 1829 and 1837, only 600 were still in post when Victoria came to the throne.

George Sole was one of those who stayed. On joining in 1834 he was posted to R Division, which covered southeast London and he served there for his entire career. He was promoted to the rank of sergeant in the mid-1840s.

Some indication of the crimes dealt with by the London police in the 1840s and 1850s can be gleaned from cases in which George gave evidence at the Old Bailey. He appeared as a witness 13 times between 1835 and 1856, mostly in trials for theft, though two involved passing counterfeit coins. In these 13 trials, the jury returned 12 verdicts of guilty and 1 of not guilty the not guilty verdict must have been a bit of a blow to George because the cost of failed prosecutions was taken from his pay. Items stolen included money, clothing, dress material, wood, various items of food, a basket, a handkerchief, lead from a roof and a lamb. For simple theft, the sentences ranged between a month and two years but the most severe sentence was reserved for Henry Porter, who in 1847 stole a lamb from a field in Mottingham and was caught with the butchered carcase he was transported for 7 years.

The Old Bailey archive records what the witnesses actually said in court and so we can read George Sole's account of what happened in these cases. For example at the trial of Ann Page for stealing two German sausages (valued at 8s) from a shop in Turpin Lane, Greenwich, he said 'I heard a cry of stop thief I ran round a corner, and saw the prisoner running I saw Killman [the shop assistant] pick up one sausage I ran after the prisoner, and she dropped this other just before I caught her.' And in a trial that could have come straight out of a Dickens novel, his evidence was 'I am a policeman. I watched the prisoner at the [Greenwich] fair, and saw him go behind the prosecutor, and put his hand into his pocket he was in the act of drawing the handkerchief out I caught hold of his hand as it was coming out of the pocket with the handkerchief he had not got it quite out.' In this case 19 year-old Henry Turby was sentenced to three months in prison.

George Sole finally retired from the Metropolitan Police on 3 March 1857, having completed 22 years of service, with a pension of £38 per year. The reason given for his retirement was kidney disease, though this clearly did not prove too serious as he lived for a further 34 years, dying at 10 Myrtle Grove, Lewisham, on 10 November 1891. George married twice: firstly to Lydia Richardson, with whom he had a son, John Howes Sole (b 1838), and then in 1873 to Sarah Barker.

Sources:

S Dell, The Victorian Policeman, Shire Publications Ltd (2008)

The Archives of the Old Bailey: www.oldbaileyonline.org

Metropolitan Police: www.met.police.uk